One reason many people never master a language is that they simply don’t put in the time. Language acquisition happens gradually, and it takes many hours of exposure to be able to speak and interact confidently. If you’re looking for “one easy hack to go from zero to fluent in 10 days,” you’ll be disappointed. There’s no such thing.

But here’s the good news: It doesn’t take any special gifts to become fluent in a new language. Anyone can do it – anyone at all. The process can be fun, natural, and engaging. In fact, the only proven method for gaining fluency demands that it be.

We’ll get to methods, but first, back to the original question: How long does it take to learn a new language? While it depends greatly on who you are and which language you are learning, we can say that it will likely take at least 600 hours of study to learn a new language, and may take over 2,000 hours.

Why does the length of time to learn a new language vary so much? Well, first of all, it depends on what language you’re trying to learn. Is the new “target language” relatively similar to your native tongue? Or totally different? Secondly, what is your goal – reading literature, having casual conversations, or something else? And finally, how are you going to go about learning it? The methods you use are critically important, probably the most frequently overlooked factor in determining how long it will take you to learn your new language.

Understanding these factors will help you identify your specific language goals and be strategic about your use of time. Let’s explore some of them in greater depth.

Why There’s No Easy Answer

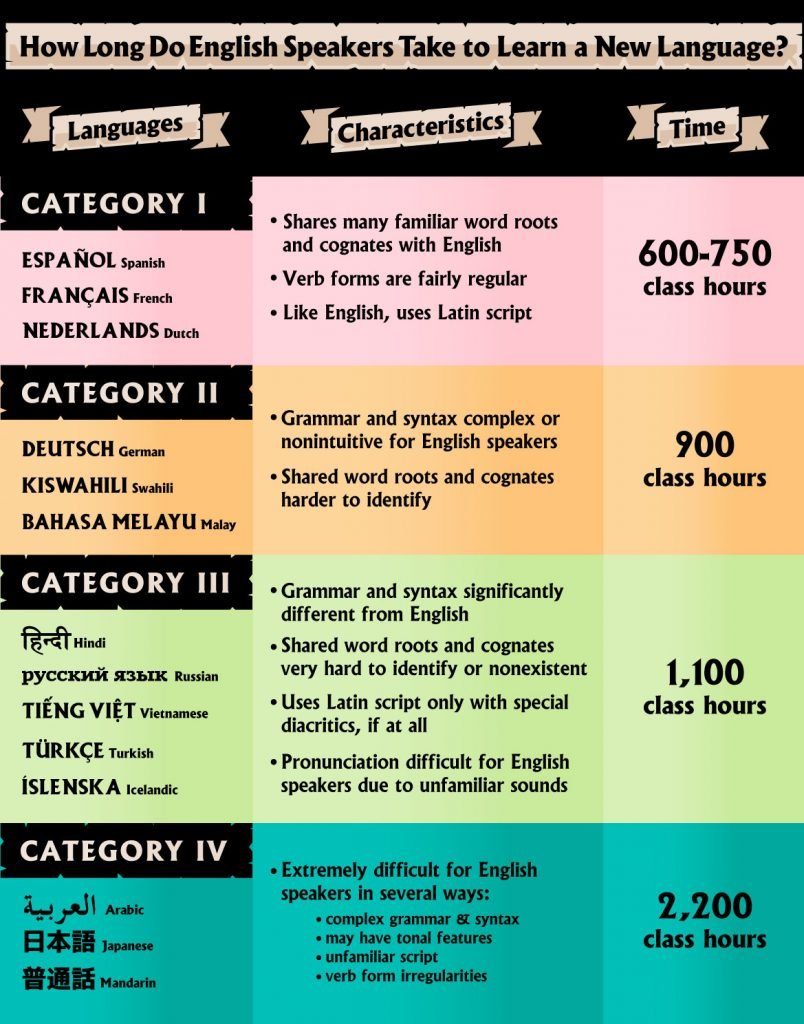

Many websites weighing in on the question of language learning times will refer you back to the U.S. Foreign Service Institute (FSI), which offers intensive language training for diplomats. The widely cited FSI table provides hour estimates for different categories of languages, ranked from I to IV based on their difficulty for native English speakers.

Category I, at the “easy” end of the spectrum, contains the popular Romance languages – such as French, Spanish, and Italian – and a few other European tongues with substantial similarities to English. At the other end are Category IV languages, such as Mandarin, Japanese, and Arabic, which FSI characterizes as “super-hard.” Most languages fall somewhere in between.

According to FSI, it takes roughly 600–750 class hours for native English speakers to achieve “Professional Working Proficiency” (see below) in Category I languages, 900 class hours in Category II, 1,100 class hours in Category III, and a whopping 2,200 class hours in Category IV.

That sounds like a lot, and it is – especially when you consider that FSI packs all this content into 24–88 weeks, depending on the language. If you wanted to get proficient in Spanish and paced yourself evenly, you’d be spending 5 hours a day in class, Monday through Friday, for half a year. To reach an equivalent level in Mandarin, you’d need to study at the same pace for nearly two years.

However, while this might reveal the relative difficulty of languages, the numbers themselves should be taken with a grain of salt. As FSI cautions, actual learning times vary based on “the language learner’s natural ability, prior linguistic experience, and time spent in the classroom.”

There are other variables, too. We’re not told what methods FSI instructors use. And as we’ll see below, many people have acquired languages without enrolling in classes – sometimes with astounding results.

How Fluent Is Fluent Enough?

Two interrelated factors that will determine how long you spend learning a language are (1) your specific goals and (2) what level of mastery you want to achieve.

Are you happy with brief conversations about everyday topics in the target language, or are you planning to attend professional conferences abroad where you’ll discuss technical subjects with international colleagues? Alternatively, maybe you just want to read great works of literature in their original language. Or perhaps your ultimate aim is to be able to compose smooth prose for journal articles, essays, or business emails.

Some famous writers have even written novels and poetry in a second language – Joseph Conrad, for example, was a native Polish speaker and didn’t learn to speak English fluently until his twenties. But that didn’t stop him from writing the novel Heart of Darkness, one of the classics of modern English fiction.

Depending, then, on what your goal is – conversing about the weather and finding a bathroom in a foreign country, reading classic poetry in the original language, or even writing the next great novel in your target language – you’ll need to devote varying amounts of time and use different learning approaches to achieve it. Whatever the case, you’ll have your work cut out for you. Fluency is no mean feat.

It’s best to think of fluency in relation to your personal language goals, not as an abstract universal standard. After all, “fluency” is a slippery term with no precise definition. Nothing illustrates this better than the situation of many immigrant children, who can speak their parents’ language at a native level of proficiency without being “fluent” according to the usual metrics.

A daughter of Indian Punjabi immigrants in Canada might speak Punjabi all day at home with perfect ease and a flawless accent. Still, if she never learned to read or write in Punjabi script (called Gurmukhi), she’s missing a basic formal indicator of “fluency.” But her grasp of Punjabi is perfectly adequate for her needs.

In the end, what matters is how well your language learning equips you for your context. Fluency should be a practical consideration, not an academic one.

That being said, there are a few widely used scales to measure overall language ability.

The Interagency Language Roundtable (ILR) and the Common European Framework of Languages (CEFR) are two common rubrics. Both use 6-tier systems (0–5 in ILR, A1–C2 in CEFR) that break down language competency into areas such as reading, spoken interaction, and listening. As the CEFR architects note, this division helps you target your learning approach strategically based on your interests.

What level should you aim for? Again, there’s no rule. But Steve Kaufmann, founder of LingQ and a competent speaker of at least 16 different languages, says he always tries to get to at least B2, variously called “Upper Intermediate,” “Vantage,” or “Professional Working Proficiency.” B2 speakers can communicate without strain and fairly spontaneously on most topics.

Steve doesn’t give a precise answer to the question of how long this takes, but he cautions that learning a language thoroughly requires – you guessed it – a lot of time. Most of all, it requires a lot of input – input that’s understandable and enjoyable. And on this, the polyglots and the researchers agree.

Learning from the Polyglots

If you want to know the best way to learn a language, it makes sense to listen to those who’ve mastered many.

Kata Lomb, a renowned Hungarian interpreter, knew more than 16 languages well enough to read foreign literature, journalism, and technical writings and serve as a paid translator. She continued acquiring new languages into her late eighties. Lomb barely traveled during her lifetime, had few language resources, and persevered despite periods of Nazi and Soviet repression.

Two of the most versatile and devoted language wizards in the world today are Alex Rawlings and Richard Simcott. Together they lead international polyglot conferences and workshops. In 2012, while still a college undergraduate, Alex was named Britain’s most multilingual student for being fluent in 11 languages. Richard speaks some 50 languages and is fluent in at least 16.

How is all of this possible? How can anyone acquire so many languages in one lifetime?

Linguist and second-language acquisition expert Stephen Krashen interviewed Lomb in 1995; he’s also investigated polyglot gatherings with Kaufmann, Simcott, Rawlings, and others to discover the secret of their success. He found that while language learners use many different tactics, they all have one thing in common. If there is a silver bullet or a magic trick for learning language, it’s this – lots of comprehensible input.

The Fastest, Most Enjoyable Way to Learn a Language

Comprehensible input refers to spoken or written content in the target language that is intelligible to the learner – it can, in other words, be understood with minimal strain and confusion. This kind of input is supreme in language learning. The more meaningful and compelling content we read and hear at an appropriate level of difficulty, the faster we pick up the language.

Lomb, according to her own account, didn’t become a polyglot through any particular genius, rigorous grammar drills, or vocabulary memorization. She simply found interesting texts in the target language – usually novels – and read them thoroughly, cover to cover. This method enabled her to learn tongues as diverse as Russian, Mandarin, and Japanese.

Although Lomb liked to browse dictionaries and explore grammar, she was adamant that it was her reading of interesting texts, not these other activities, that had propelled her to fluency.

Those of us who’d be happy just to speak one other language well – instead of ten or twenty – can draw inspiration from another Krashen story. Armando, a Mexican immigrant to Los Angeles, spoke modern Hebrew fluently after 12 years of working at an Israeli restaurant. He’d never studied the language and couldn’t explain its grammar, but he spoke spontaneously and with a near-perfect accent. His secret? Hearing Hebrew day in, day out, in a friendly environment.

READ MORE: How We Teach Ancient Languages

Krashen’s interactions with multilingual people over many decades have confirmed his theory of language acquisition: People acquire language not through forced study but by understanding relevant messages. We need to hear and read things that we can make sense of, things that hold our attention. We need comprehensible input.

So how long will it take you to excel in your chosen language? No one can say. But one thing’s certain: The fastest way to learn is also the most fun and engaging. Find some colorful children’s books, pick an inspiring TV series, or listen to a thought-provoking podcast in the target language (or better, all three!). Get absorbed into the content to the point that you forget it’s not in English. When you suddenly realize you’ve lost track of time, that’s when you know it’s working.

The Ancient Language Institute exists to aid students in the language learning journey through online instruction, innovative curriculum, and accessible scholarship about the ancient world and its languages. Are you interested in learning an ancient language?