People often say that Latin is a dead language. So why bother learning it? But what does it mean for a language to be dead, exactly? Languages aren’t organisms, and they don’t die like them, either. They don’t have a pulse we can check. So how do we know when a language has actually died?

For animals, death is a final affair — a non-erase punctuation mark. You’re either alive or you’re not. Do languages like Latin behave the same way, or are there different “levels” of death? To quote the greatest film ever made: “There’s a big difference between mostly dead and all dead.” Is Latin really dead, or is it “slightly alive”? And supposing it is “all dead,” can it rise again?

This is an autopsy of the Latin language. Our story begins in the Roman Empire. But spoiler warning: It doesn’t end there.

The Fall of the Roman Empire

After its founding in 753 BC, the Roman Empire endured for about 1,000 years. The founder of Rome was the legendary Romulus and the last Roman Emperor was Romulus Augustus, so the Empire begins and ends with a Romulus. But the Latin language did not die immediately with the Empire. It would linger on as a living language for another 500 years, at least.

Nobody knows why the Roman Empire collapsed. Current research seems to indicate the Roman population had diminished drastically at the beginning of the fifth century. Maybe this contributed to its weakness. In any event, the territory where Latin was spoken went from being a single empire with a single emperor to being a collection of states, most of which were ruled by invading Germanic kings.

READ MORE: How Old is Latin?

As barbarian hordes helped themselves to the Empire, Rome’s profile began to change. The famous Roman army was disbanded. People no longer had to pay taxes, but this meant the loss of civil services like military protection. Trade was at depression-era levels. Towns were left empty as Rome’s reduced population moved into the countryside, where they would have little contact with the outside world. In short, Rome now looked much like her neighboring nations — except with ruins memorializing older days of glory.

In 476 AD, the barbarian statesman, Odoacer, struck home the final nail in the coffin by deposing the Roman Emperor and making himself the King of Italy. Now every ruler in Italy’s many states was Germanic, not Roman.

The Germanic tribes did not simply plunder the empire, burn the houses, enslave the people, and go back home. Instead, they moved in. Wherever they conquered, they built farms and raised families. The second thing to remember is that there were a lot of different Germanic tribes. Franks, Vandals, Burgundians, Goths, Lombards, Visigoths — the list goes on! And each had their own language.

At this point, you’re probably thinking that this must have been when Latin died. But the truth is more interesting.

We don’t know much about these Germanic languages because, in a short time, they all disappeared. This is remarkable. In history, the trend is the conquered adopt the speech of the conquerors. In Rome at this time, the reverse happened: The Germanic invaders start speaking Latin!

Why this happened is puzzling since the language of the invaders would have been the closest to power. Then again, the invaders were the minority in Italy. And as they built houses and reared children, they were surrounded by native late Latin speakers. (The famous exception is England, where Latin did not survive.)

The Death(?) of Latin

When did Latin die? To oversimplify the matter, Latin began to die out in the 6th century shortly after the fall of Rome in 476 A.D. The fall of Rome precipitated the fragmentation of the empire, which allowed distinct local Latin dialects to develop, dialects which eventually transformed into the modern Romance languages.

In a sense, then, Latin never died — it simply changed. So Latin did not die when Rome fell. Rome’s fall merely began this process of change.

After all, how do we know when a language has died? The most commonplace answer is: “When it is no longer spoken as a first language.” So to know Latin’s time of death, we need to figure out when the last generation of native Latin speakers died out.

But this is a complicated question. No one agrees when Latin died, or if it died at all. But if it did die, then it died slowly of natural causes. There are two main contributing factors that determined Latin’s development after the fall of the Roman Empire.

First, after Rome fell, the inhabitants abandoned the cities and towns and moved into the countryside. There, the Latin-speaking peoples were isolated from other people groups — including fellow groups of native Latin-speakers.

Now, it was normal for people to spend their entire lives within a few square miles of farmland. As we’ve said before, to create a distinct language, all you have to do is form a small tribe and live without contact with other groups for a time. This did not spell the death of Latin, but after a few hundred years distinct Latin dialects began to emerge from these villages.

Second, people stopped using written Latin. Putting a language to writing, and consulting prior works in the same language, tends to slow a language’s rate of change. For instance, Shakespeare probably would have a hard time understanding modern English. We use words he would not recognize, like google or hermeneutic. English has changed a lot since his time. But it would have changed a lot more if each generation of students weren’t required to read Shakespeare in high school. Reading old books keeps us in touch with earlier forms of our language. It helps standardize our vernacular. Well into the 6th century, you could still find writers who wrote Latin according to the old models. But this gradually changed. Writing became less common. Schools slowly vanished except in a few Italian towns.

People traveled less often. Contact between towns was kept to a minimum. While writing did not disappear entirely (thanks in large part to Christianity, which we will get into later), written Latin had less and less influence as fewer people learned to read or write.

In short, there was nothing to hinder the development of local dialects. These could vary across regions, or even from town to town. Historians think the most rapid change occurred from the 6th to the 11th centuries. (For this reason, some websites will point to the center and say that Latin must have died in the 8th or 9th century. But this is arbitrary. It has more to do with people’s desire for a concrete “time of death” than with real historical evidence.)

Little by little, decade by decade, these changes accumulated to such an extent that people who lived on different ends of the former Empire were no longer able to communicate with each other.

So, Latin did not die so much as change. And what it changed into is the modern Romance languages like Romanian, French, Portuguese, Spanish, and of course, Italian. In a sense, saying that Latin is dead is like saying English is dead because no one speaks Old English anymore. Perhaps we’d think differently if we called it Old Italian instead of Latin.

The Rise of Christianity

We’ve charted when Latin “died,” but how did it survive for so long? And why do people still learn to speak it?

The answer has to do with a small, disliked religion in the Empire that worshipped as God a poor, young Jewish man from Galilee. The enemies of this religion called it Christianity (see Acts 26:28). But the Christians called themselves Ecclesia: the Church. The first Christians were Jews and the Church got its start in synagogues. But it preached a message of universal salvation and from an early period drew converts from all walks of life. Justin Martyr, an early Christian apologist and convert from paganism, wrote to the emperor, Marcus Aurelius, that the Church was comprised of “men of every race” (First Apology, 1.1). This was written around 150 AD, so from an early period, the Church was diverse (if small) and drawing imperial attention.

As the Roman Empire weakened in the centuries leading up to its collapse, Christianity grew stronger. As we’ve said, Rome collapsed in the late-5th century. By the 6th century, most of the former empire was populated by Christians. By the 7th century, Christian missionaries were making inroads into neighboring tribes, re-establishing connections that had been lost when the Empire fell.

Christians were people of a Book. With one or two exceptions, no religion in the ancient world concentrated so much on a sacred text in its thinking, liturgy, and spirituality like Christianity and Judaism. Of course, this text was the Bible. This commitment to the Bible, and the eagerness of Christians to share its message with all nations, would be a leading factor in Latin’s continued survival.

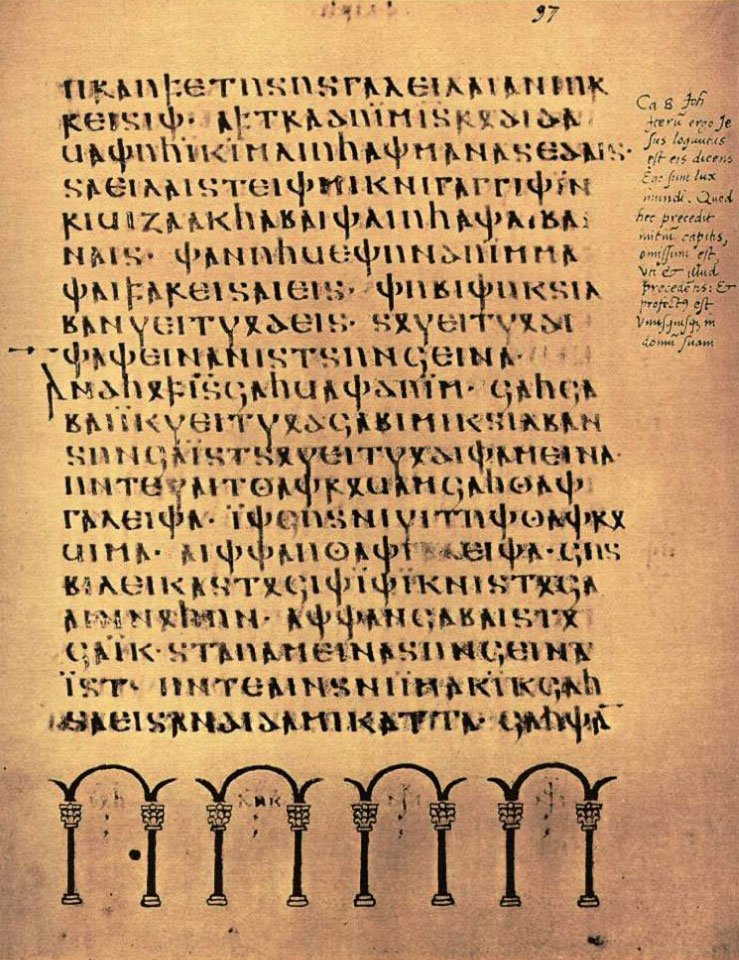

Jerome was a Church Father who spoke Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. In the late-4th century — a mere century before Rome’s collapse — he was commissioned by Pope Damasus to translate the Bible into Latin. For the next two decades, this was his biggest project. Despite popular opinion, Jerome’s translation was not the first Latin Bible. There were many Old Latin Bibles in circulation. Jerome’s job was to produce a corrected standard edition. His translation would not catch on at first, but it grew in authority over time. He would not complete the project, but others after him would continue his work. The eventual result would be the Vulgate Bible.

As Christian missionaries interacted with Germanic people, they needed to learn the local languages. More importantly, they needed to translate the Bible into their vernacular.

In the 4th century, a Goth-Greek archbishop named Ulfilas translated the Greek Bible into Gothic. The Goths were one of the Germanic tribes living in what is known today as the Balkans. Only fragments of this Gothic Bible remain today, but according to his biographer, Ulfilas had translated the Bible in its entirety — excluding only the books of Samuel and Kings. (Ulfilas thought these books were too violent to be edifying to the war-like Goths.)

The Gothic Bible would be copied and read for several centuries. The most famous copy still extant, the Codex Argenteus, features silver ink and purple-dyed parchment. The text is a literal, word-for-word translation from Greek. The Codex Argenteus was commissioned by Theodoric the Great in the 6th century. He also commissioned a Latin Bible to match. While the Goths enjoyed a Bible in their own vernacular, in Church they worshipped in Latin.

Shortly after Theodoric died, Gothic rule over Italy collapsed in a series of wars with the eastern Roman Empire. The last Gothic king would be killed in 553 CE. These events spelled the death of the Gothic language and, in Christian communities, made Jerome’s Latin Bible more and more authoritative.

While writing and reading were declining everywhere else, in the Christian Church these things were being preserved. This kept a live connection with the Old Latin of the Roman Empire. While Latin disappeared in some regions or transformed into Italian or Spanish in others, in the Church Jerome’s Bible was still being read and copied and distributed — along with other early texts. The Church thus became an archive, preserving civilization and learning while the world spiraled into war and economic depression. This was especially the case in Celtic regions.

The result? Two languages began to be spoken in society simultaneously. Beginning as the language of the Church, of the liturgy, and of the Bible, Latin expanded to become also the language of learning and administration. Meanwhile, the Germanic and Romance languages were spoken in daily use.

This “two-language” society would endure into the middle ages and up to the present day. This is why Latin became the official language of the Roman Catholic Church. If you visit Vatican City today, you will find the Roman Catholic Church still publishes all major documents and decisions in Latin. Today, just like in the time of Theodoric, the Roman Catholic Church is an international institution. Knowing Latin helps them overcome many language barriers.

However, the preservation was not perfect. Over time, a distinctive form of Latin emerged within Christendom called Ecclesiastical Latin. While in most ways identical with early Latin, Ecclesiastical Latin is based on later Italian pronunciation, borrowed vocabulary from both Classical Latin (the Latin that appears in great works of literature) and Vulgar Latin (the everyday Latin spoken by common folk), and imbued these Latin words with stronger theological meaning.

These developments would occur during the medieval period, so Ecclesiastical Latin is occasionally identified as Medieval Latin. This is a bit inaccurate, since the Church continues to speak it today! If you attend a Latin Mass in your city, it will be conducted in this unique ecclesial pronunciation. Classical writers like Cicero probably wouldn’t recognize it as his native Latin, but he wouldn’t think they were different languages, either.

But now it is time to revisit an earlier question: Once a language has “died,” can it be resurrected? Can Latin be spoken as a first language again?

Latin as a (Modern) First Language

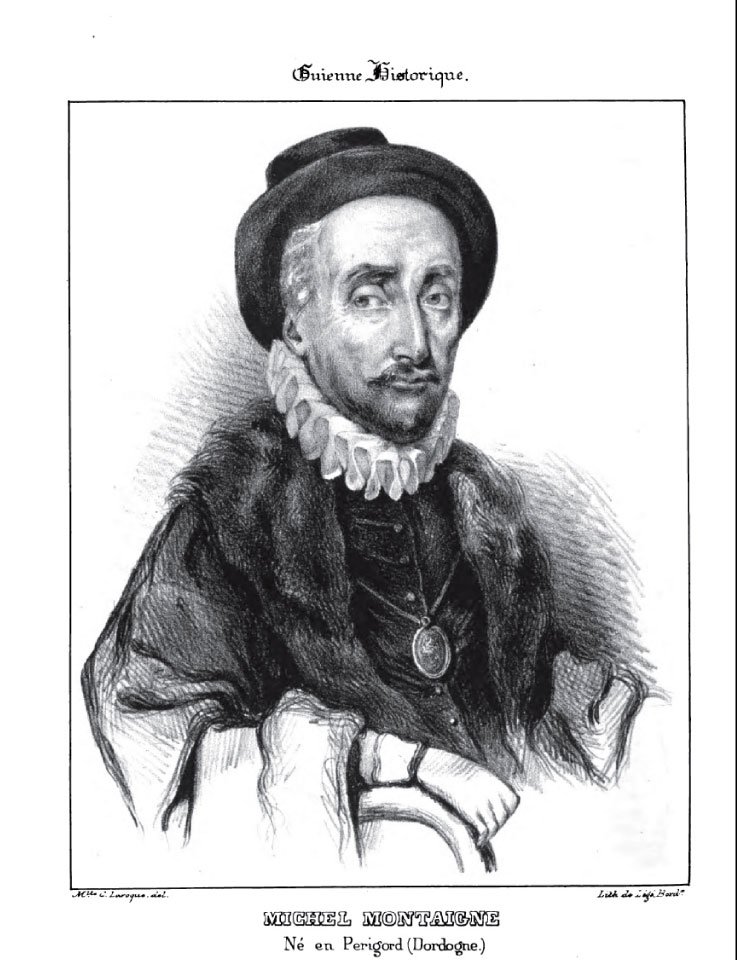

In the 1530s, close to Bordeaux, France, the essayist Michel de Montaigne was born. Today, Montaigne is best known for his masterpiece, Essays — a collection of reflective pieces that make excellent armchair reading even today. Montaigne was born at the intersection of various historical movements. In the two decades before his birth, Martin Luther had defended himself at the Diet of Worms, Michelangelo had placed the finishing dabs on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, and Christopher Columbus had died back in his home in Valladolid, Spain.

What do all of these figures have in common? They all spoke Latin. And they all spoke it as a second language. That is, they grew up learning German or Italian or Spanish — the language of their homeland — then they had to learn Latin in a classroom. Luther, Michelangelo, Columbus, and anyone else in politics, academia, or trade had to learn at least a little of it. Latin was like a glue holding Europe together, conducting a lively correspondence over linguistic, cultural, and intellectual barriers.

What does Montaigne have to do with the death of Latin? Well, Montaigne was born to fiercely Humanist parents. Humanists had a deep love for classical culture and literature. They heavily emphasized the importance of learning classical languages like Greek and Latin.

What makes Montaigne remarkable is that he was the subject of a Humanist experiment conducted by his parents. They had an infatuation with Roman culture that they shared with many others of their time. Command of beautiful and grammatically perfect classical Latin was the highest goal of a Humanist education. It wasn’t just the language of the academy and the church. It unlocked the door to the ancient world, which Humanists deemed the locus of all human wisdom.

The experiment? To bring up Montaigne as a native Latin speaker. That is, Montaigne’s French parents wanted French to be their son’s second language. How did they attempt this? As soon as Montaigne was weaned from his wet-nurse, his parents hired a German named Dr. Horst. While no native, Horst could read and write Latin flawlessly. He knew almost no French, which was just as well. No one was allowed to speak to Montaigne except in Latin, including his parents.

In one of his essays reflecting on the experiment, the adult Montaigne wrote:

My father and mother learned enough Latin in this way to understand it, and acquired sufficient skill to use it when necessary, as did also the servants who were most attached to my service. Altogether, we Latinized ourselves so much that it overflowed all the way to our villages on every side, where there still remains several Latin names for artisans and tools that have taken root by usage. As for me, I was over six before I understood any more French or Perigordian than Arabic.

The idea was to raise Montaigne with Latin as a first language. The approach was intended to be organic: Montaigne would learn Latin the way all people learn their first language, by simply hearing it spoken and trying to speak it — and not to speak it like we so often do in classrooms through make-believe scenarios. Montaigne had to learn Latin to explain himself, make requests, socialize, or convey urgent information. Acquisition is most rapid when there are stakes.

Today, we might find this approach extreme — even a little cruel. But at the time, it was commonplace for tutors to bore young Latin students with endless rote memorization, and then whip them when they made mistakes. We can detect the gratitude from Montaigne when he wrote he learned Latin “without artificial means, without a book, without grammar or precept, without the whip, and without tears.”

On one hand, the experiment was a failure. His parents could not possibly isolate him from any exposure to languages other than Latin until he was six — not with servants running around, visits to the market, interactions with other children and adults, etc. Montaigne never achieved native proficiency — largely because he never met native speakers!

On the other hand, the experiment was a success. Montaigne gained a greater mastery of Latin than his later tutors. He retained this mastery throughout his life by revisiting classical writers and poets. He had a special fondness for Virgil. Even late in life, when his father fainted from a kidney-stone attack, Montaigne exclaimed in Latin — not French — as he caught his father in his arms.

The experiment to raise the first native Latin speaker in a thousand years was the vision of Montaigne’s eccentric father, Pierre. It’s unclear if children were being subjected to similar experiments in other Humanist households, but at any rate, other Humanists would have approved of the experiment and they would have been interested in the results.

Most households likely stuck to “artificial means.” This remains the case today. Though whips aren’t involved, most modern Latin courses emphasize rote memorization. This does not always translate into language proficiency. However, a few courses can still be found which use a more “natural” method.

The Death(s) of Latin

The story of Montaigne points to the various ways we can answer: When did Latin die? First, we must define death. And for a language, there are gradations of death. The first death is no one speaks Latin as a first language. The second is no one speaks Latin at all.

The latter is the most extreme form of death for a language. Scholars call it “extinction.” This is when a language is little more than a memory. We know people spoke it once. Maybe we could study it, but learning a language is not the same thing as speaking it. It’s the same difference between knowing something and putting it to good use. If a language never leaves a study, if it is not being used, it is totally dead.

READ MORE: Is Latin a Dead Language?

Sadly, many ancient languages underwent total death. But this obviously does not describe Latin. Latin is more than remembered or studied. People continue to speak and learn Latin today. So it is not dead in the total sense.

The first kind of death is the loss of native Latin speakers. Usually, this is enough to kill any language totally. The last generation to speak Latin as a first language never really died out, so much as transformed, but somehow, Latin endured and has enjoyed a career as the most alive dead language of the past 1,500 years. Latin is not merely a Mother Tongue which lives on only “in spirit” through its descendants. It is simply an earlier evolution of the Romance languages and of Ecclesiastical Latin at the Vatican.

In an importance sense, Latin never died. So learning Latin today is less like resurrecting the dead and more like looking at an old photo of modern Indo-European languages.

The Ancient Language Institute exists to aid students in the language learning journey through online instruction, innovative curriculum, and accessible scholarship about the ancient world and its languages. Are you interested in learning an ancient language?