“It’s all Greek to me.”

“Latin is a language, dead as dead can be, first it killed the Romans, now it’s killing me.”

Ancient languages have a reputation for difficulty. As ancient language teachers, we are pretty familiar with the complaints uttered by generation after generation of students. Even in late antiquity, the grandson of the poet and rhetorician Ausonius of Bordeaux complained about the difficulty of studying Latin and Greek at the same time: “To have to learn two languages at once is alright for the clever ones and gives excellent results, but for an average mind like mine such dispersion of effort soon becomes very tiring.”

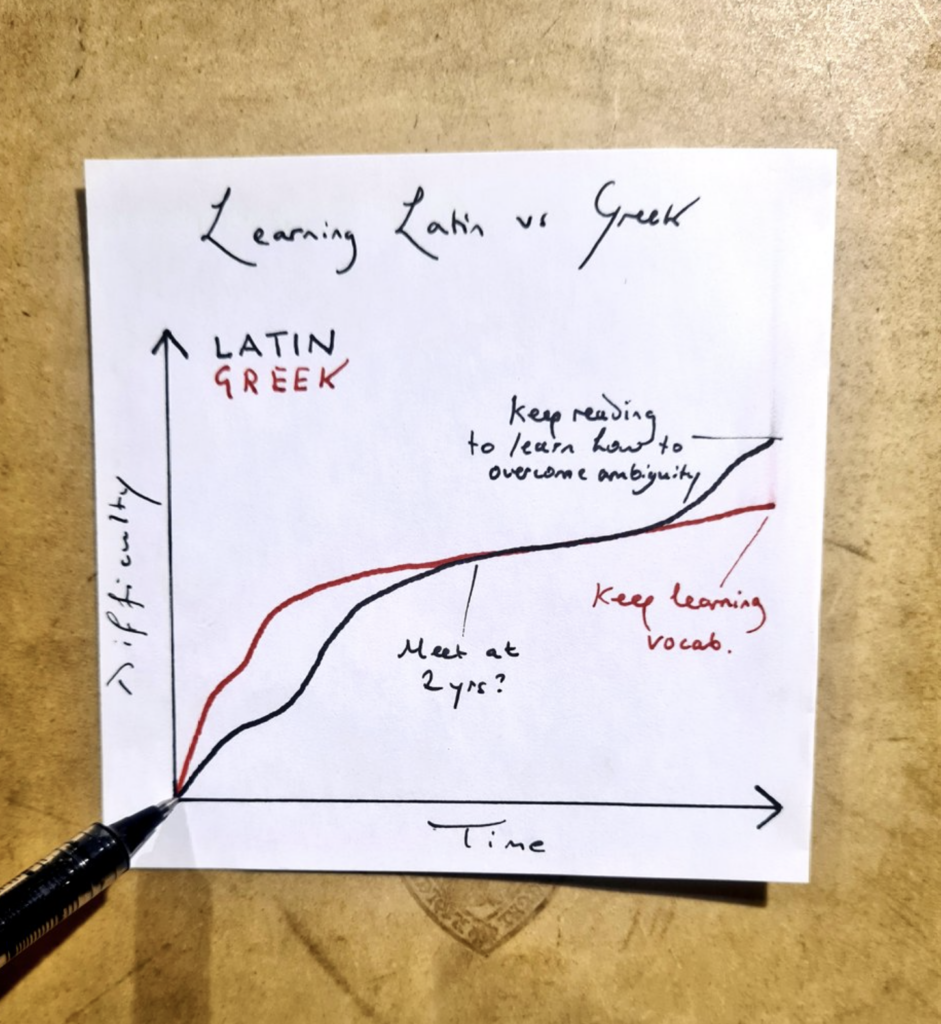

Because they’re often paired in curricula, it’s natural to compare the relative difficulty of Latin and Greek. Antigone Journal shared a hand-drawn graph on X comparing the difficulty of learning each language over time.

Wherever you come down on the Latin vs. Greek question, that graph’s very sharp vertical curve of difficulty which Greek presents to beginners seems accurate. Getting started with Ancient Greek is super hard.

Compare with Latin: Thousands of people have, like me, had the magical experience of picking up Hans Ørberg’s Lingua Latina Per Se Illustrata and reading the first chapter with almost complete understanding despite having zero prior Latin training. Ørberg has shown that for Latin, the curve does not have to be so steep at the beginning. No such book or curriculum exists for Ancient Greek, however. Many attempts have been made, but none – in my view – have come close to being as good as Lingua Latina.

That is why the Ancient Language Institute has not offered Ancient Greek classes for kids. We have been running elementary, middle, and high school level Latin classes for years, but Ancient Greek has remained the domain of college students, grad students, and adults. We have never been satisfied with the beginner-level materials that exist, and do not trust that they can provide an adequately gentle on-ramp to the language for our younger students.

So we decided to change that. We believe we have succeeded, and for that reason, will be running our first-ever High School Ancient Greek classes this upcoming fall. If you have a high schooler, we hope you will consider enrolling them; regardless, I hope you will continue reading to take a little tour of the curriculum and see what we have built for our younger Ancient Greek students.

Ancient Greek Vocabulary by the Direct Method

As the first great language textbook author, John Amos Comenius, demonstrated in his 17th century Latin textbook Orbis Pictus, language should always be taught with images. Languages are made out of words; words refer to realities. It is always better to point to a tree and say τὸ δένδρον than it is to say “δένδρον means tree.” After all, the word “tree” is just the English word that refers to the same reality that τὸ δένδρον refers to. The sooner you can get away from giving English equivalencies for Greek words, the better. As C.S. Lewis wrote about learning Greek in his memoir, Surprised by Joy:

Those in whom the Greek word lives only while they are hunting for it in the lexicon, and who then substitute the English word for it, are not reading the Greek at all; they are only solving a puzzle. The very formula, ‘Naus means a ship,’ is wrong. Naus and ship both mean a thing, they do not mean one another. Behind Naus, as behind navis or naca, we want to have a picture of a dark, slender mass with sail or oars, climbing the ridges, with no officious English word intruding.

Out with the vocab lists, in with images. We have partnered with Picta Dicta, the language curriculum company founded by Timothy Griffith, the eminent Latinist at New St. Andrew’s College, to create the curricular skeleton for our high school Greek program. Griffith’s curricular work is heavily influenced by Comenius (as you might guess from the company name) as well as W.H.D. Rouse’s writings and methods. Every single vocabulary term in our program is introduced with an image and audio.

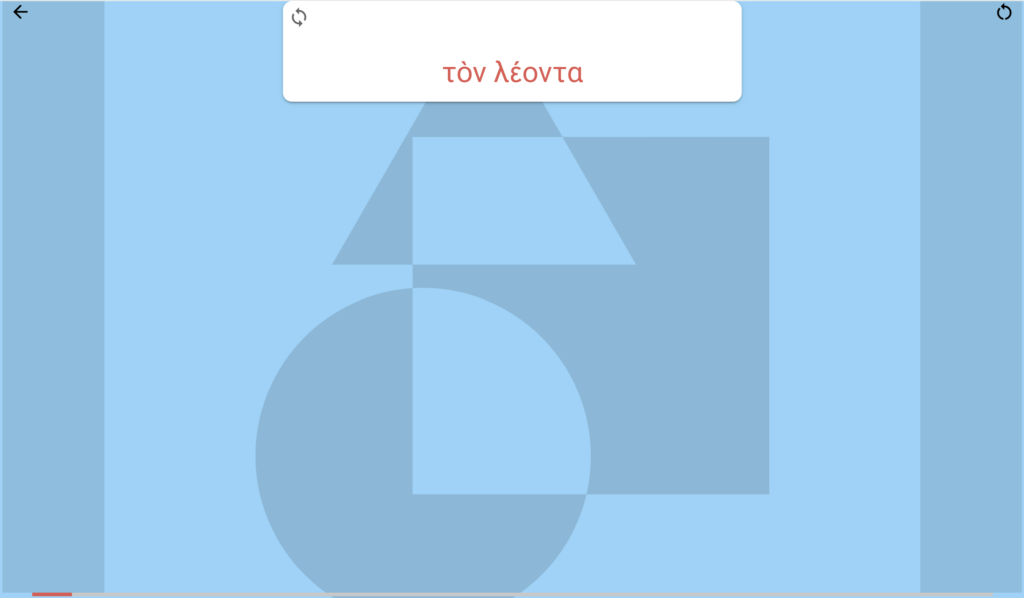

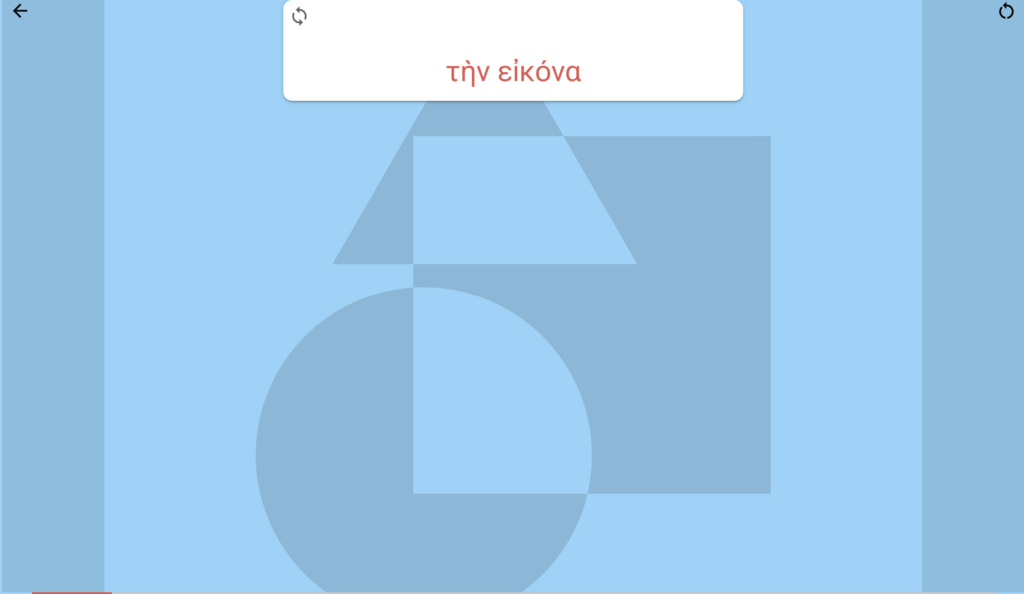

The first time a student encounters a term, they see the word in Greek and hear audio of it being said (with careful attention to pitch accent, vowel quantity, and aspirated vs. unaspirated consonants):

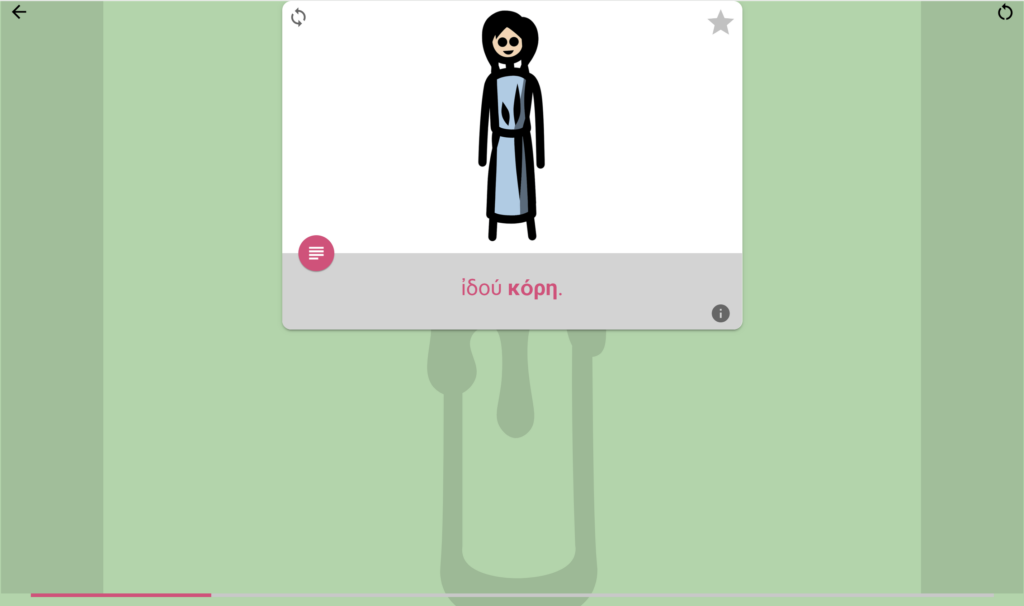

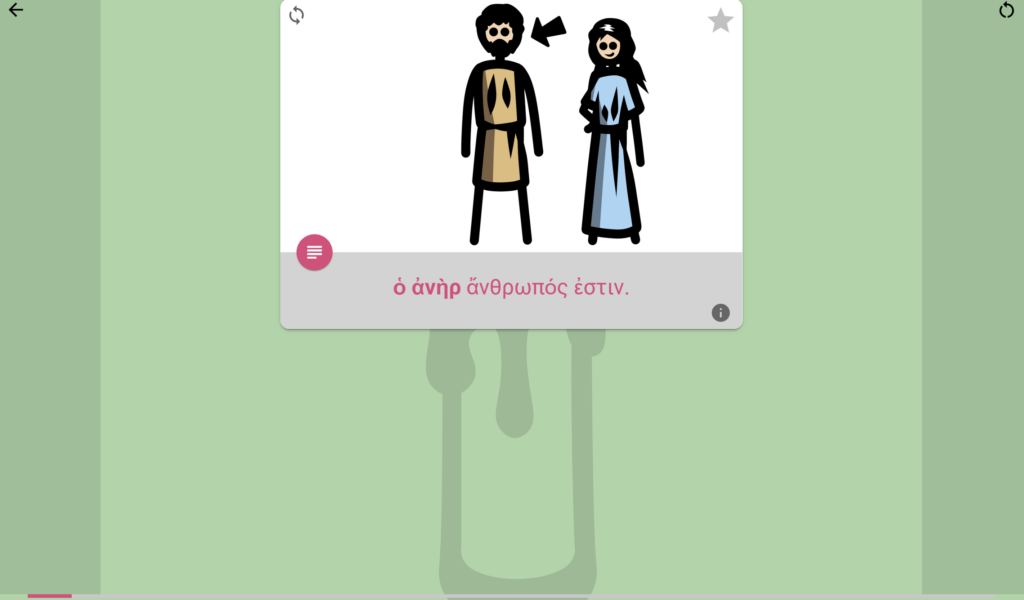

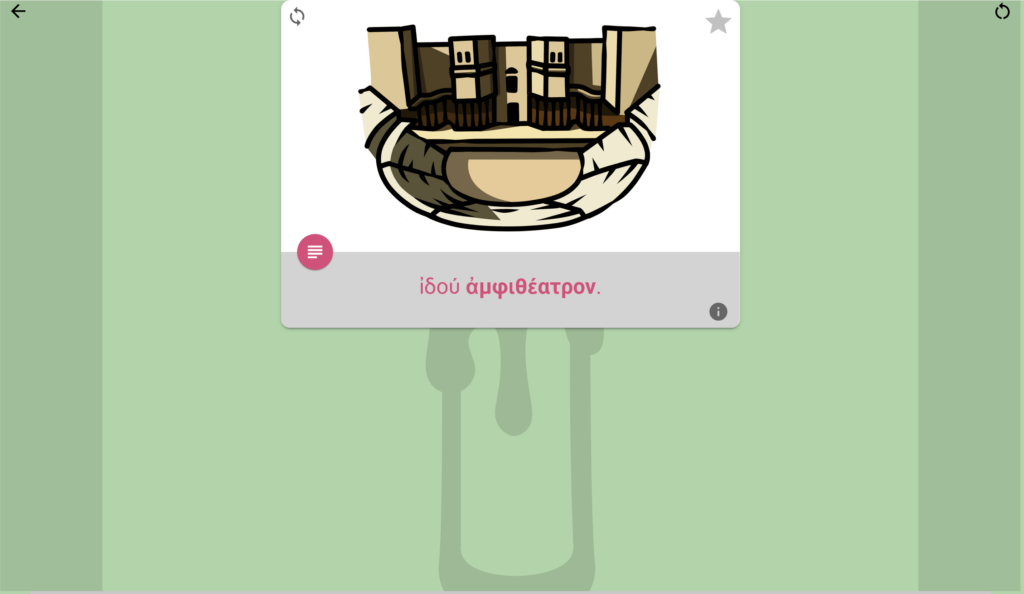

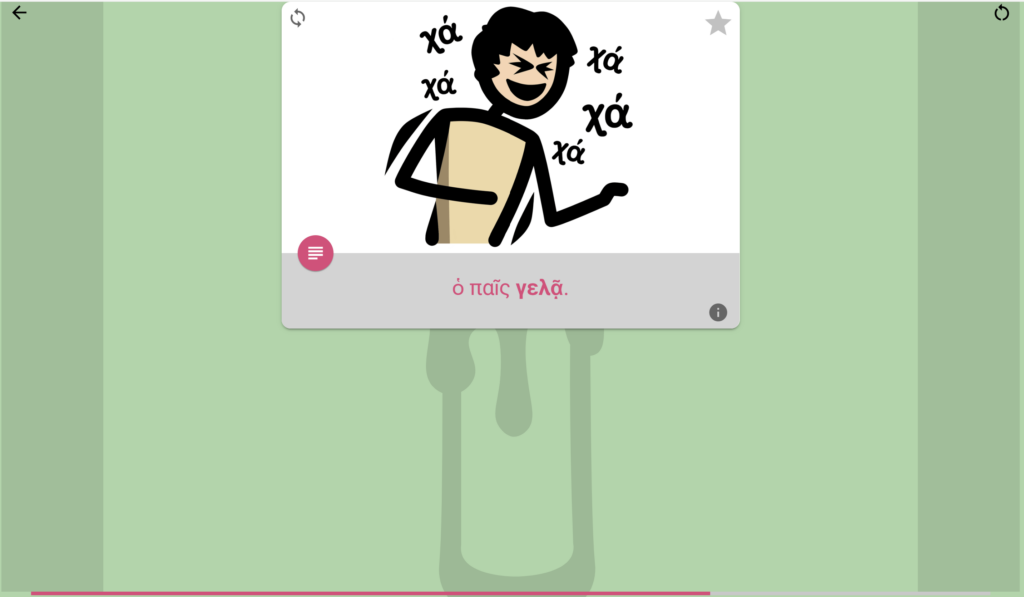

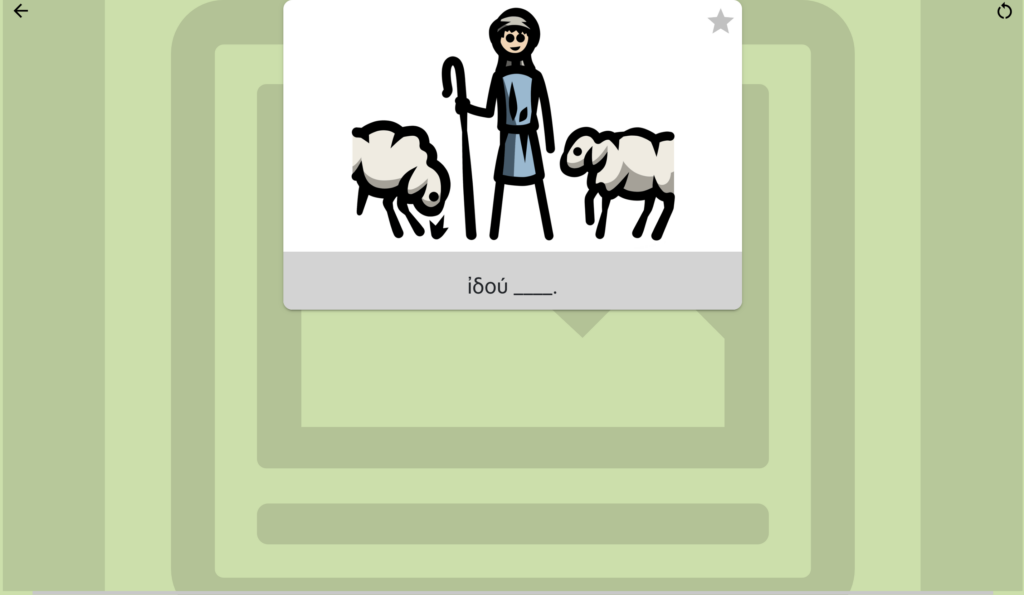

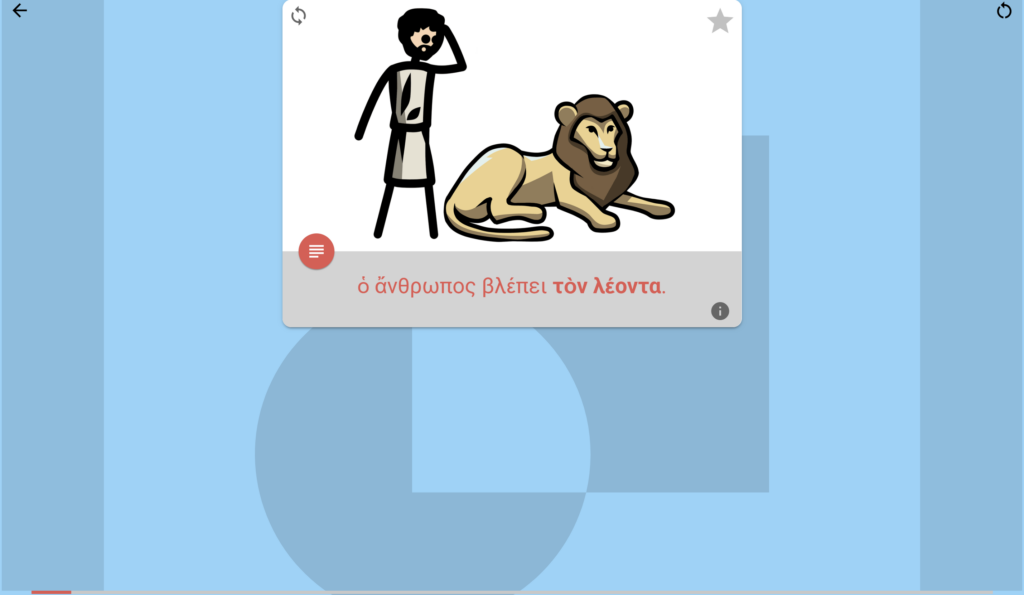

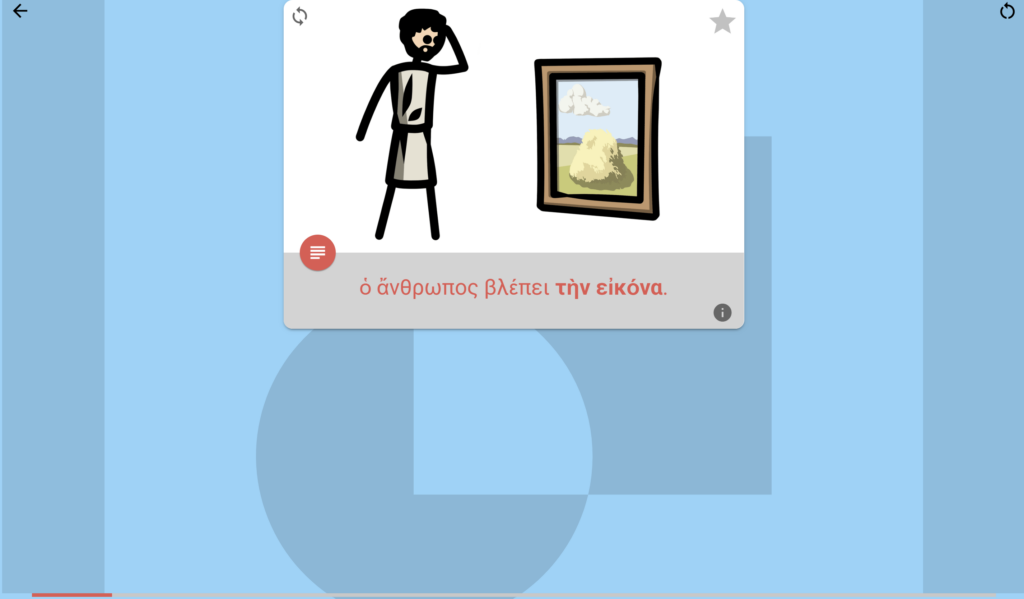

The “flashcard” then flips over, to reveal an image for that term, along with a simple phrase or sentence using the term, accompanied again with audio:

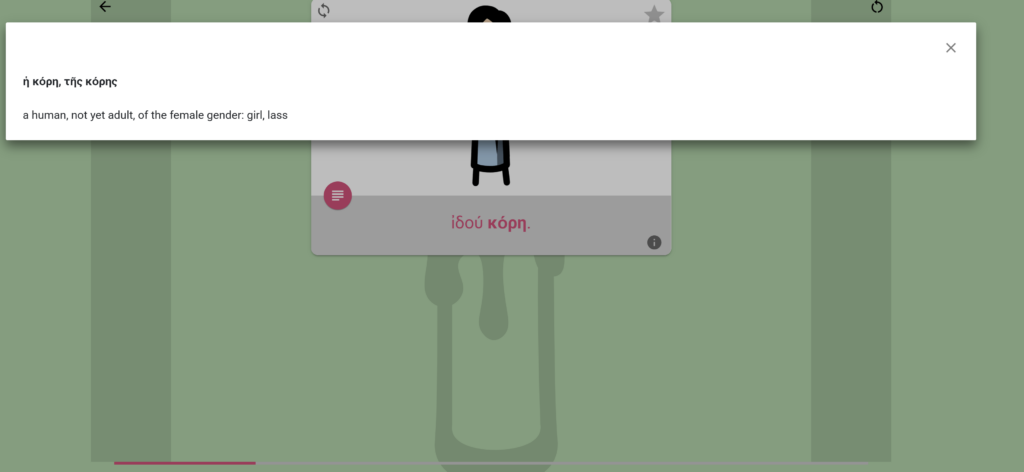

Pictures are better than translations, but sometimes they’re not always clear. On any of these digital “flashcards” students can click the pink button for an English definition that, by its length is meant to be forgotten. Ideally, the mental link between the Greek word and the concept will survive, and the English gloss will fall away:

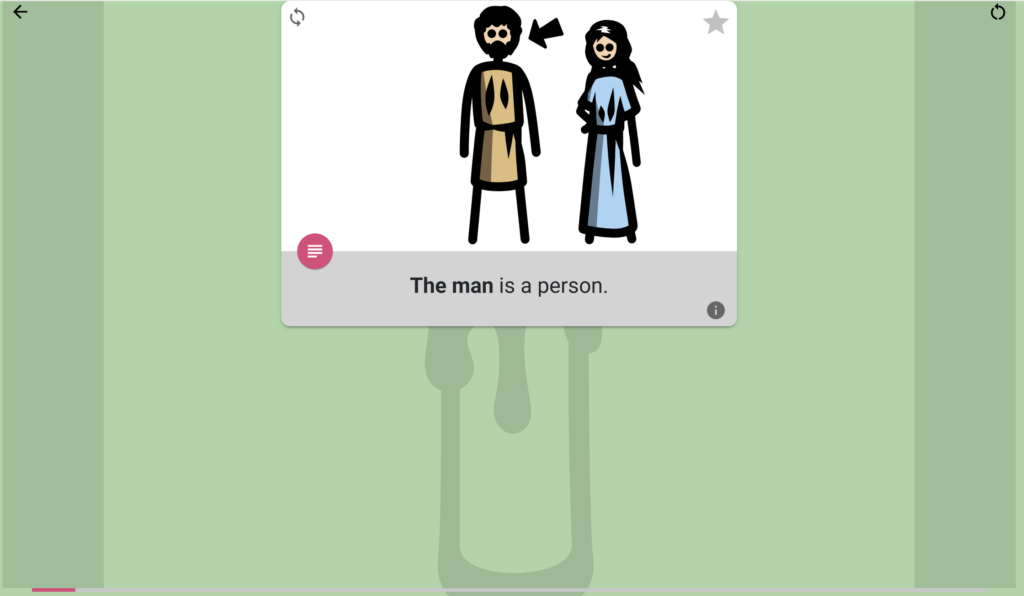

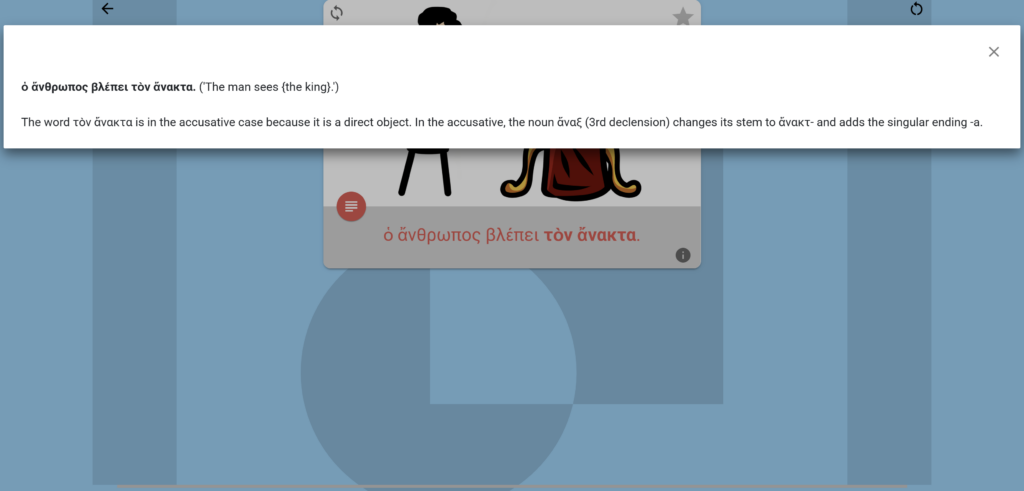

If they wish, students can also click the unobtrusive little “i” icon to see an English translation of the little phrase or sentence:

Here are a few more vocabulary cards, just to give you a taste:

The platform also enables us to quiz students on the new vocabulary they have learned, using a variety of matching games. On this one, students see an image, and then have to select the correct answer out of six possible options:

Grammar by the Direct Method

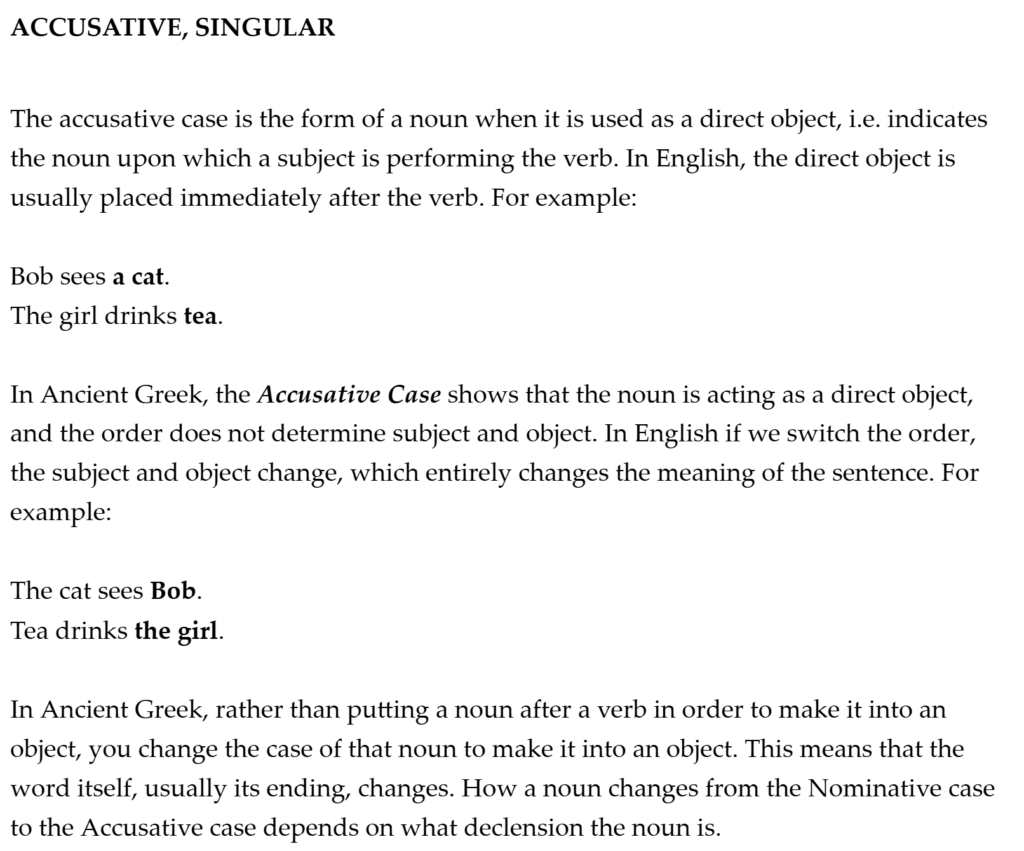

Introducing vocabulary by the Direct Method is fairly straightforward: Present a student with a picture of a boy holding a staff surrounded by sheep, tell him “ἰδού ὁ ποιμήν”, and repeat. But what about grammar?

After all, it is the constantly shifting forms of Greek words that account for so much of the language’s difficulty. Can you teach grammar in a similar way, without immediate resort to charts and brute force memorization?

When we talk about “grammar” we are talking about the patterns that grammarians have observed: the many ways that the language creates meaning through things like stem changes, case endings, and verb endings. Using the Direct Method to teach grammar really boils down to making students aware of those grammatical patterns through meaningful communication (rather than totally abstract charts). You can do this in much the same way that you introduce vocabulary. First of all, we use terms that have already been introduced as vocabulary in the grammar activities. That way, they see the transformations of already familiar words.

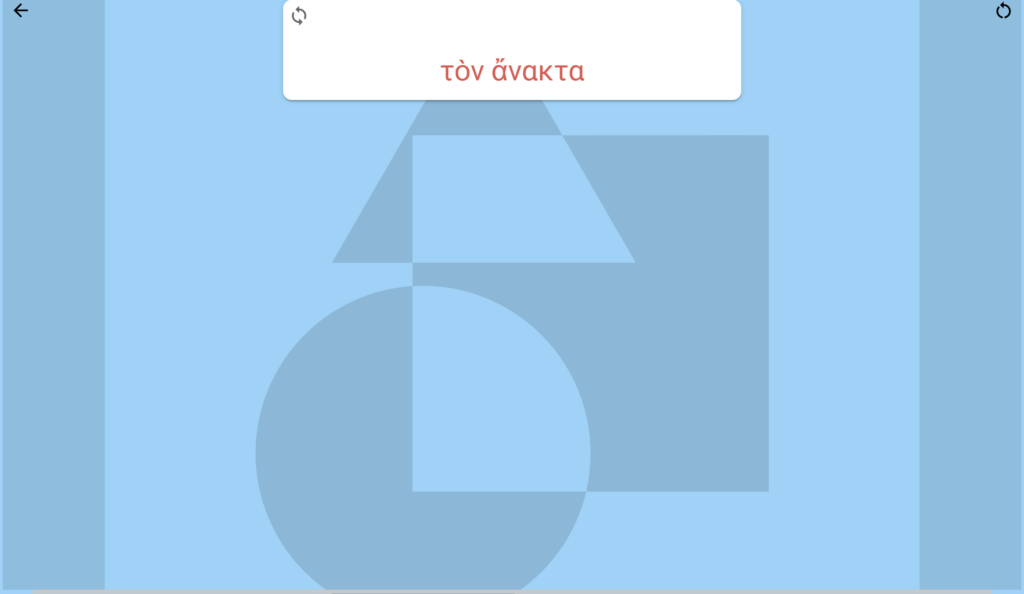

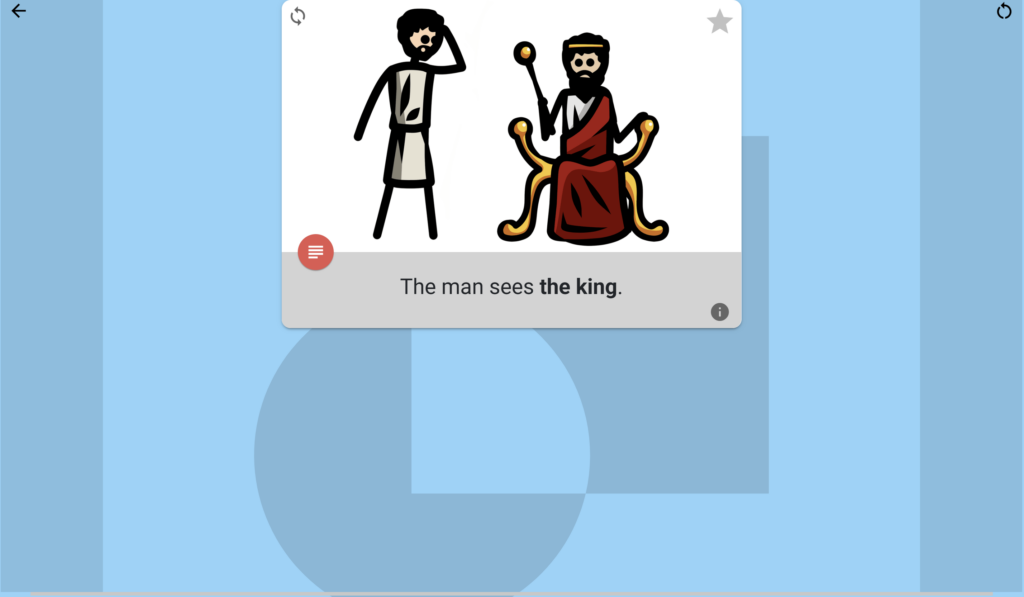

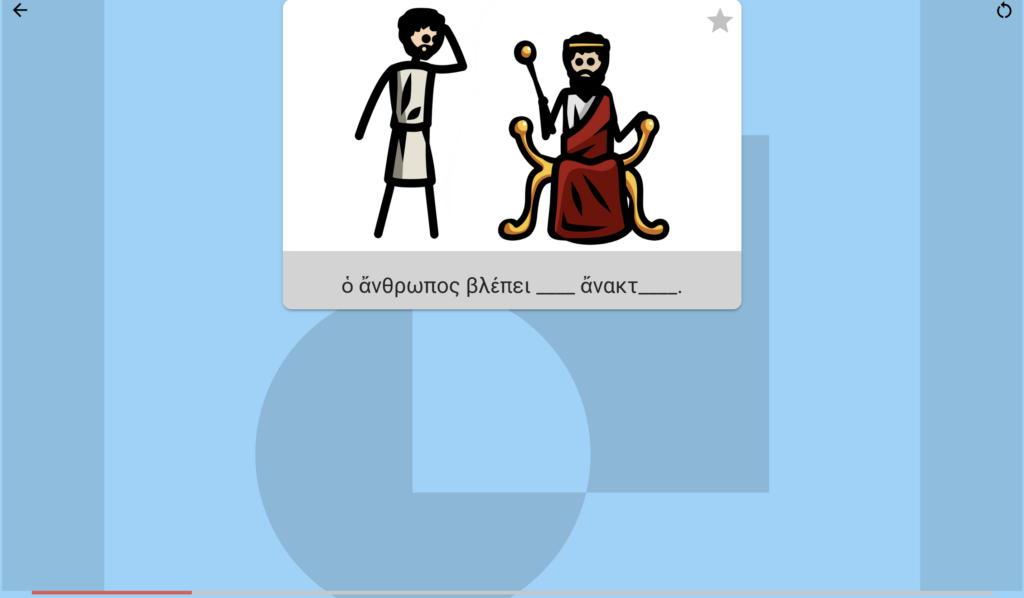

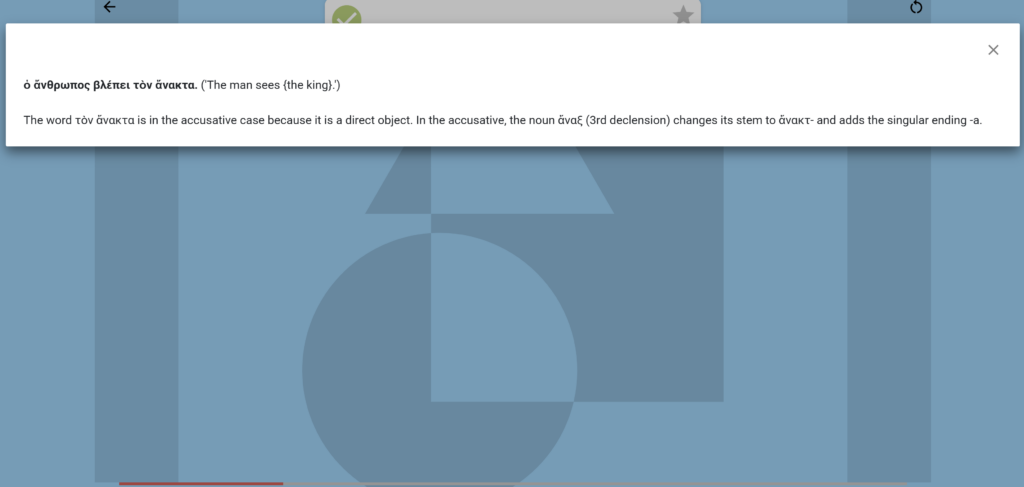

Here’s how we introduce the 3rd declension accusative. First, show an example of a 3rd declension noun declined into the accusative case:

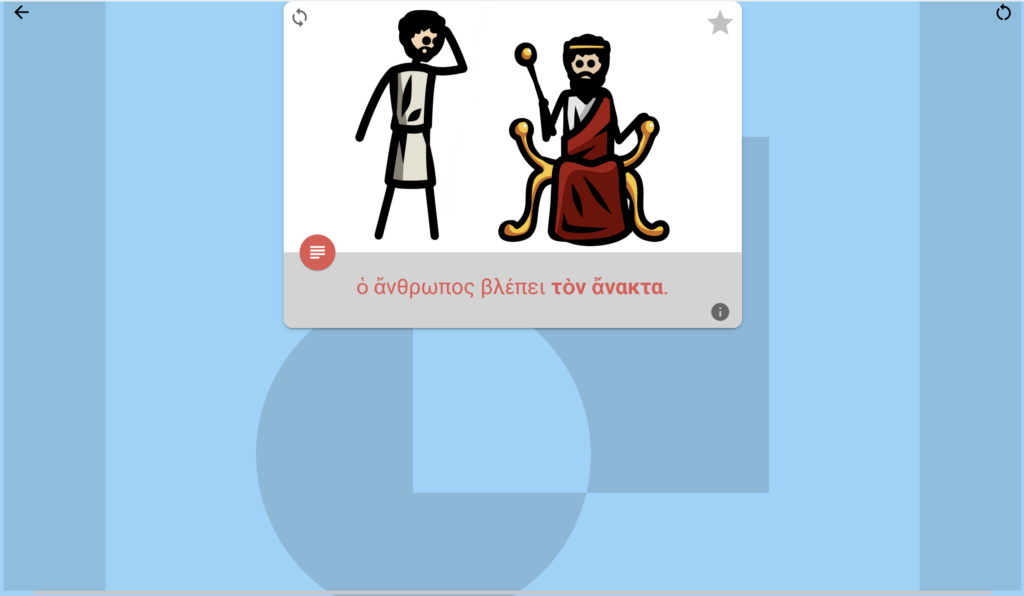

Then, show that 3rd declension accusative noun in the context of a meaningful sentence – once again with an image and audio.

When students get to this exercise in particular, they will have already learned all the vocabulary that appears: ἄνθρωπος, ἄναξ, βλέπει. But the progression is sequenced and graded for conceptual difficulty as well. The 3rd declension of nouns is a bit trickier than that of 1st and 2nd declension; so, when we introduce 3rd declension accusatives, students have already been introduced to the concept of the accusative and how nouns decline, with exercises and explanations using the 1st and 2nd declension. That way, when we get to the 3rd declension, we have eliminated some of the “conceptual noise,” so that students can focus on the particularities of the 3rd declension accusative (rather than, say, simultaneously learning about what a direct object is).

Like with vocabulary, so with grammar: we’re not fundamentalists about the Direct Method. We’re happy to let students “opt in” to seeing English explanations and translations:

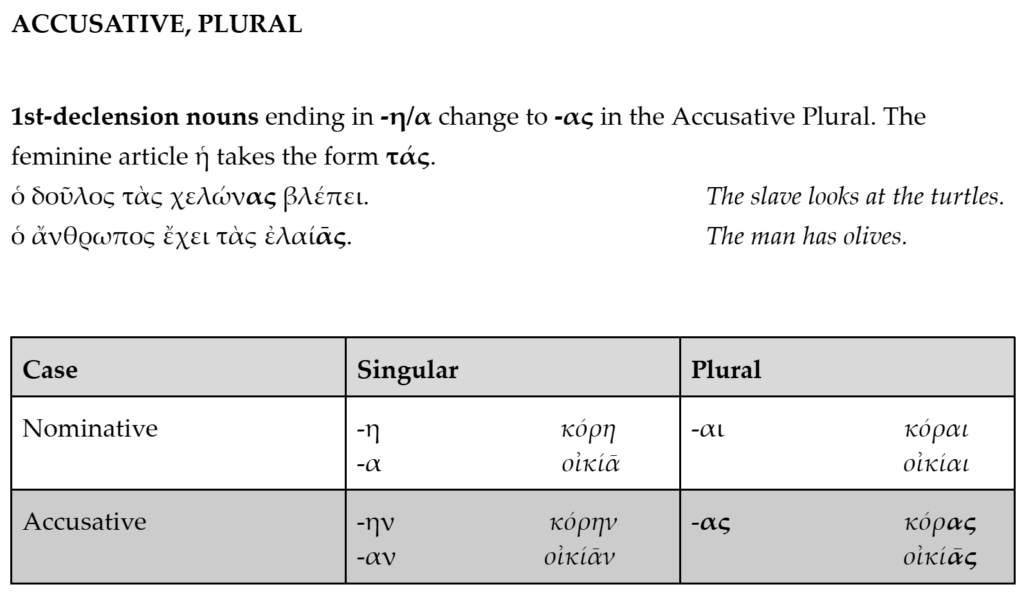

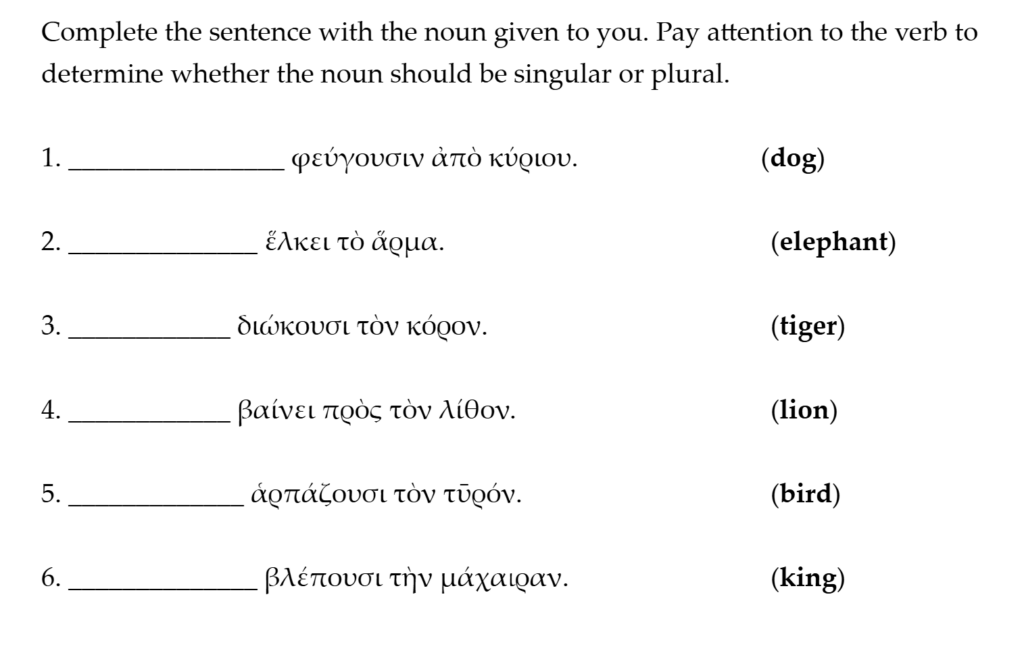

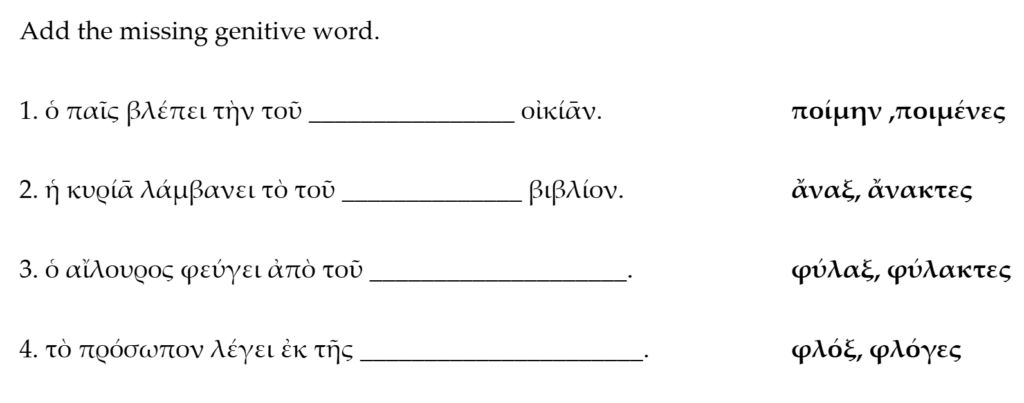

With enough repetitions of the same pattern – with special care taken not to introduce too much extra conceptual “noise” – students begin to internalize the grammatical form they are learning:

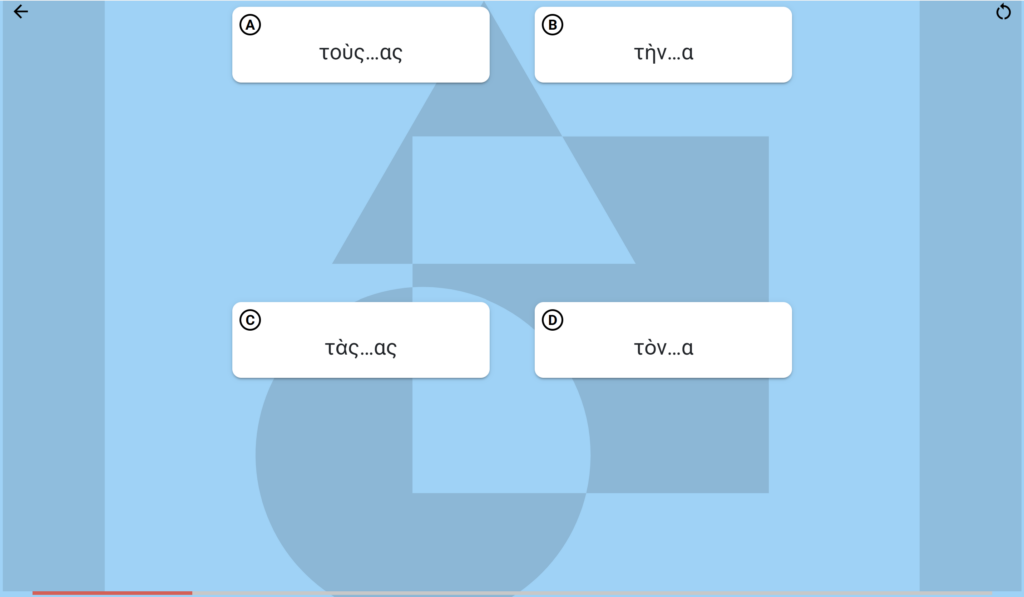

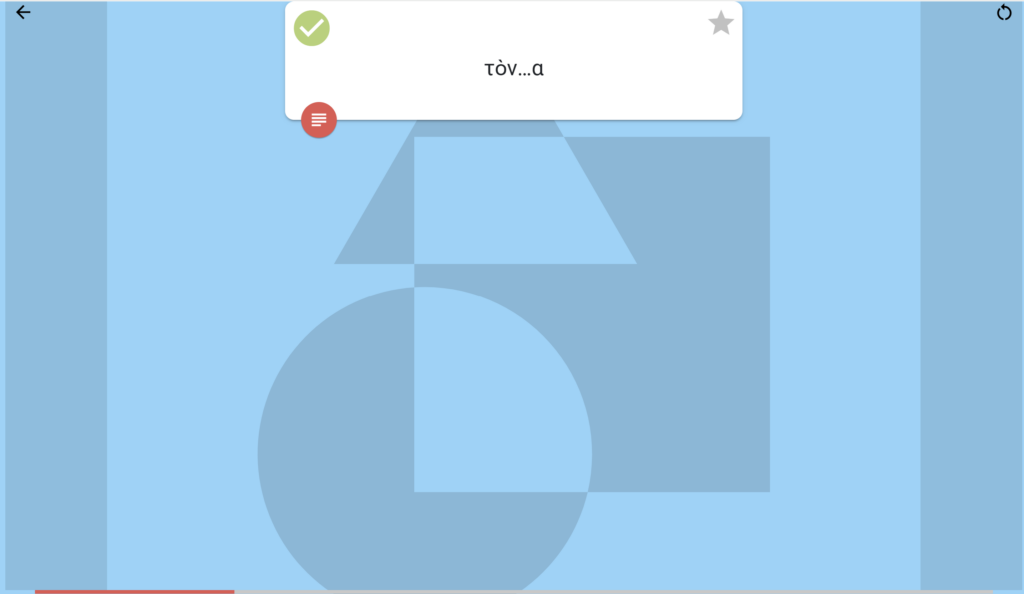

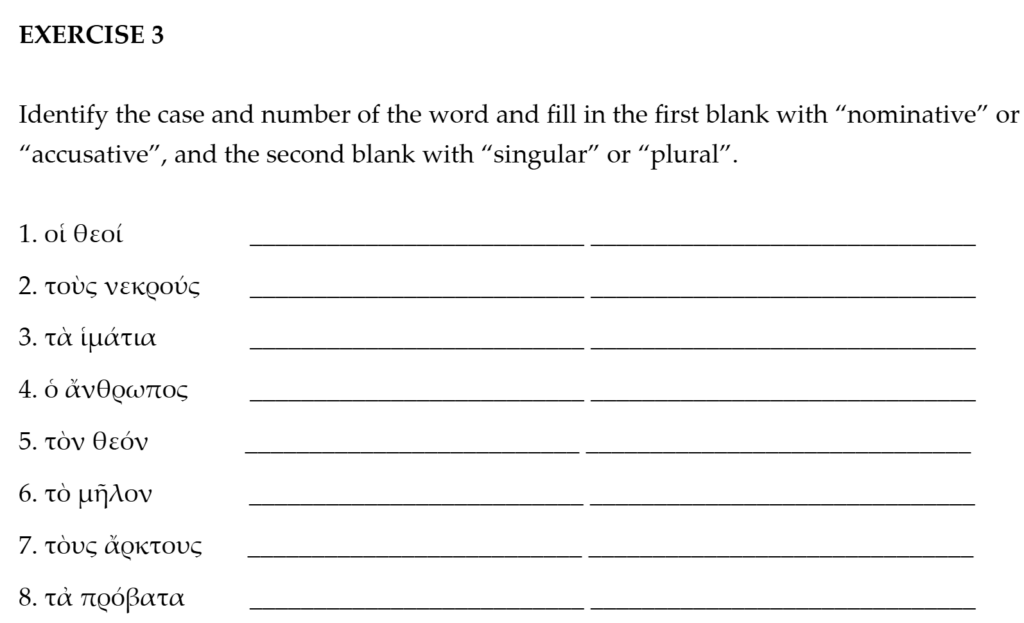

As with vocabulary, the Picta Dicta platform quizzes students on the grammatical patterns they are learning. Critically, all of the quiz activities focus on recognition rather than typing. At this level (and especially for this age) students would move so slowly through any Greek-typing activity that they would spend too much time hunting for the right key rather than reading, hearing, and internalizing the Ancient Greek language. But by simply clicking on the right answer, they are getting the chance to read and understand a ton of comprehensible Greek – and get corrected when they get it wrong:

Grammar Workbook Companion

The most important pathways for a language into a student’s mind are through pictures and audio. That said, we also believe that giving explicit grammar explanations can be immensely helpful. English-language explanations should not replace the Direct Method of showing students words and patterns in meaningful contexts; but those explanations can certainly supplement.

We’ve developed a simple workbook with explanations and activities of each concept and pattern introduced on the digital platform, so that students get an extra round of practice. The digital platform follows a 15-lesson sequence (to be expanded to 30), introducing vocabulary and grammar in a very gradual progression. The workbook follows the same progression.

Of course, a year’s worth of gently graded Greek study does not come close to covering the full panoply of the Greek verbal system, for example. What we’re offering to our high school Greek students is not a Zero-to-Aeschylus program in a year. What it does, however, is smooth out that impossibly steep grade that beginning Greek students – especially young beginners – face when they first encounter the language. We wanted a way to give young, beginner students the ability to internalize lots of core Ancient Greek vocabulary, recognize and correctly produce the basics of Ancient Greek grammar, and synthesize that vocabulary and grammar knowledge into fluent reading of texts written in Ancient Greek. That is what this program does.

One of the other critical mental pathways for language acquisition is writing things out by hand. That is another reason we developed this workbook to accompany the digital platform. The digital platform is perfect for presenting students with lots of audio and images. What it does not do is give students the opportunity to make Greek appear on paper with their body. So in this workbook we have included lots of simple exercises that require students to write in Ancient Greek as well – as often as possible in the context of meaningful communication.

You Learn Greek in Order to Read

Acquiring an ancient vocabulary is cool. Learning Ancient Greek grammar might be an end in and of itself for a handful of grammarians. But the real reason to study Ancient Greek is to read dialogues, poems, histories, plays (and more!) written in Ancient Greek.

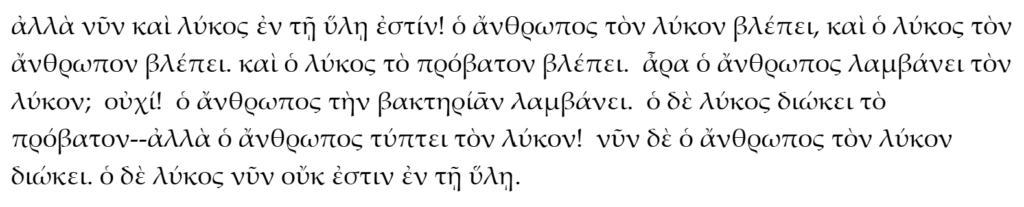

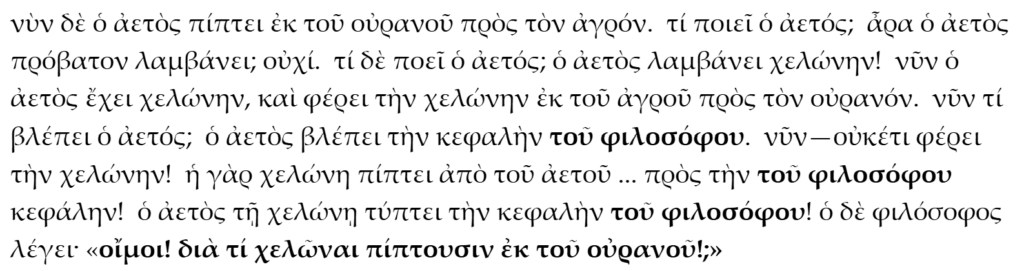

The vocabulary and grammar progression in the Picta Dicta platform and in the workbook supplement is built around the simple Greek stories we’ve written for beginner Greek students. ALI Greek & Latin Fellow Leo Hunt wrote these stories to be simple, comprehensible, and entertaining. Yeah, it’s not Aeschylus, but it’s important for beginner students to read Ancient Greek and see how the vocabulary and grammar that they have studied combine to create meaning, and to get practice reading and thinking in Greek – rather than translating in order to understand.

If you keep students away from comprehensible texts until they can understand Aeschylus, you’re going to keep them away from Greek for a long time. And by doing so, Greek will remain a dead artifact, hidden behind museum glass, which students cannot touch, cannot understand on a visceral level. Words and concepts abstracted from meaningful communication are just the elements of a code, not a language.

We have built this program in order to make Ancient Greek come alive, so that students are able to read, think, and speak in Ancient Greek. We’re excited to get started. For now, the curriculum is available only by signing up for a course that uses it. In partnership with Picta Dicta, we do plan to offer it for sale in the future, though there is not yet a planned date for retail sale. In the meantime, we hope you’ll consider joining us for High School Ancient Greek!

High School Ancient Greek 1

Wish your young student could read the Greek New Testament, or Plato’s dialogues, or Homer’s epics, in the original Greek? Don’t know where to start? Let us take care of it. Whatever you want your high schooler to read, this course is your starting point. Using the brand-new curriculum ALI designed in partnership with Picta Dicta, and targeted at providing an intuitive introduction to the Greek language for high school students, this course will introduce students to 300+ Greek vocabulary terms, all noun cases and declensions, and the basics of Greek verbs.