Learn Biblical Hebrew. Learn fast, have fun.

Have you heard seminary students groan about the difficulty of Biblical Hebrew? Do the dreaded right-to-left script and totally unfamiliar alphabet make you want to give up before you’ve even started?

Biblical Hebrew—also called Ancient Hebrew or Old Testament Hebrew—sometimes gets a bad rap. However, that has more to do with ineffective teaching methods than anything else. When you learn Biblical Hebrew with ALI, you’ll be able to read Old Testament literature sooner and more directly than you could have imagined.

Skip the standard monotonous Hebrew courses—where you’re not expected to become fluent anyway—and become a confident navigator of Hebrew texts.

What’s our secret? Ditching the usual methods.

Using our cutting-edge, interactive digital textbook and live online classes, students will find that Biblical Hebrew comes to life.

No matter your age, education level, or career pursuits, we’ll help you craft a plan for mastering Hebrew that’s perfectly suited to your unique learning goals.

What Level of Hebrew Student Are You?

Beginner

This course is best for students who have no prior experience with Hebrew. Read, write, and speak in Hebrew from day one. You will learn grammar and vocabulary with an interactive digital textbook and meet in a live, online class.

Intermediate

This course is best for students who have some experience with Hebrew, but aren’t yet comfortable reading the Hebrew Bible. By the end of this course, you will be reading selections from the Hebrew Bible with ease!

Advanced

This course is designed for students with at least two years of Hebrew under their belts. Students will customize their own curriculum and pursue the biblical texts that most interest them. This course equips you for independent study!

How We Teach Hebrew

In most Biblical Hebrew courses, you could sit through weeks of rote memorization before ever reading a real text from the Old Testament. Even then, texts tend to be very short selections, and they take a back seat to paradigms, vocabulary, and grammar. Too many students complete a course with only a set of “conversion formulas” to show for it, and they think they’ve learned Hebrew!

That’s like memorizing a recipe from a cookbook and saying you’re a chef—even though you’ve never set foot in a kitchen.

We think there’s a better way.

Proficiency in Old Testament Hebrew requires reading early, much, and often. In our courses, you start reading Hebrew as soon as possible, and reading, not rote memorization, is the priority.

That’s our recipe for success. And that’s why the Ancient Language Institute exists.

†††

Jonathan Roberts, Founder and Director of the Ancient Language Institute

“It’s a pity to hear budding scholars grumble about the trials and travails of learning Biblical Hebrew. Usually that’s because they’ve been laboring in a monotonous classroom environment, using stale methods that treat the Hebrew language as a set of ciphers rather than a beautiful and dynamic tongue. We know there’s a better way! Acquire Ancient Hebrew through class conversations, creative language learning software, and actual readings—not by flipping pages in a lexicon or sweating through grammar charts. When you learn with ALI, you’ll be amazed at how quickly and directly you're able to understand biblical texts in the original tongue.”

†††

ALI’s Natural Method

The ALI curriculum is built around Active Pedagogy and Comprehensible Input.

- With Active Pedagogy, language students learn by reading, writing, and speaking the target language from the beginning. Memorization of vocabulary, grammar rules, and other critical material happens dynamically with fun and interesting texts.

- With Comprehensible Input, language students read enjoyable, understandable texts at an appropriate level of difficulty. They digest entire stories from beginning to end without needing to run to a dictionary. This prolonged exposure to the language compels the brain to make sense of messages before understanding how the language works—which is how everybody learns their first language as infants! This is the only proven way to acquire fluency.

†††

What You Can Expect

At the introductory level, all students receive a license to our interactive, digital textbook, which helps you learn Ancient Hebrew grammar and vocabulary according to the Direct Method. At every level, actual class meetings take place live, online. Our Fellows will present lessons, oversee exercises, and lead students in readings and discussions, so you’ll get a chance to interact with our faculty and other students.

Since our goal is to help you read Ancient Hebrew fluently, we’ll get you reading texts from the Jewish Scriptures as quickly as possible. And even though modern Hebrew (the national language of the state of Israel) is the only version of the language with a native community of speakers today, you will learn to speak Biblical Hebrew in our classes, too! One of the best ways to learn how to read is to practice speaking, and vice versa.

You don’t need the gift of tongues to acquire Hebrew. It requires no special skill or innate talent—just good study habits and time. And that’s all we expect of students. We’ll take care of the rest.

The ALI Promise

We promise to be a student-first educational institution. Here’s what that means:

- We build class schedules only after you sign up. This way, we can work around your calendar and commitments. (And yes, no matter the time zone. Our student body is spread across the world.)

- We’re here to meet your goals—not the other way around. We conduct individual consultations with all new or prospective students so that we meet your personal language goals, whatever they might be.

- We only assign work that’s useful for achieving fluency as fast as possible. Our methods represent the leading research on second-language acquisition. With ALI, you begin to read, acquire, and understand Hebrew from day one.

What is Biblical Hebrew?

Hebrew is a Semitic language, part of the same language family as Arabic and Amharic.

Like any language that’s been around for thousands of years, Hebrew has undergone major changes. But because Jews diligently transmitted, studied, and commented on the texts of the Hebrew Bible—also known as the Tanakh or the Old Testament, depending on your tradition—the Hebrew language outlasted many ancient relatives, such as Ugaritic and Akkadian.

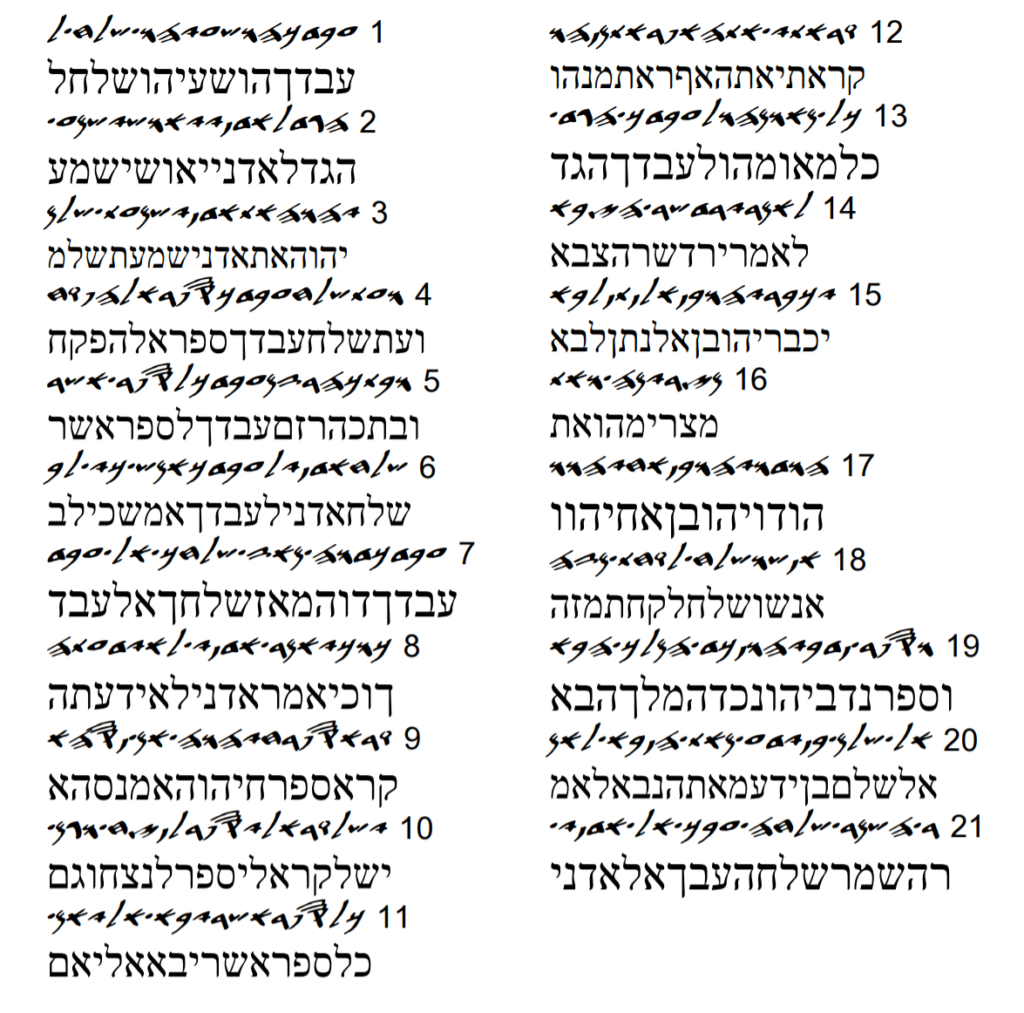

Pre-Modern Hebrew can be divided into roughly three forms or stages: Paleo-Hebrew, Biblical Hebrew, and Mishnaic (or Rabbinic) Hebrew.

The earliest Hebrew writing, dating to the tenth century BC, used a picture-based Phoenician script that scholars call Paleo-Hebrew. It appears in ancient inscriptions from the biblical land of Canaan, which became the territory of Israel and Judah.

While archaeologists might learn Paleo-Hebrew to decode old documents like deeds and letters, the average Ancient Hebrew student won’t need it for reading texts. The biblical manuscripts we have today (with a handful of exceptions) were composed and copied in the later Hebrew alphabet.

The Hebrew alphabet we’re used to seeing, known as “square script” or “block script,” originated during the Babylonian exile (597–538 BC). When the Israelite nobles and priests were taken into captivity, they borrowed from the Aramaic writing style of the Assyrians and Babylonians to write and copy their sacred texts.

Over the next few centuries, this newer script gradually replaced the older Paleo-Hebrew system. When we refer to Biblical Hebrew, we’re talking about the 22-letter Hebrew square script as it was used in biblical texts and the accompanying spoken language.

By the time of Biblical Hebrew, case endings had disappeared, and the usual word order had settled into verb-subject-object (“Ate Adam the fruit”). We don’t know exactly how the language was pronounced, but it probably made ample use of emphatic consonants like pharyngeals and glottals, similar to Arabic. Nouns, pronouns, verbs, and adjectives were all either masculine or feminine.

Like its Semitic relatives, Biblical Hebrew is built around primitive word roots of two or three consonants forming the basis for nouns, verbs, and adjectives that all stem from the same fundamental image or concept. This makes for some good wordplay. In Isaiah 7:9, for instance, when King Ahaz is fretting about his enemies, God sends the prophet to go and tell him to buck up: “If you don’t stand firm [ta’aminu], you won’t be established [te’amenu].” He’s playing on the image of building or strengthening behind the verb aman—from which we get “Amen.”

One of Biblical Hebrew’s quirks, which lends itself to ambiguity, is the existence of only two verb tenses: perfect (a completed action) and imperfect (an incomplete action). Determining precisely when something happened or will happen can be tricky. Usually context clues us in to the meaning, but not always. Take God’s mysterious self-revelation to Moses in Exodus 3:14: “Ehyeh asher ehyeh—I am who I am.” Or is it “I will be who I will be”? We don’t know. Needless to say, the obscurity of this statement has prompted endless discussion by Jewish scholars and mystics.

By about the third century BC, the dominant regional tongue of Aramaic had all but supplanted Hebrew in speech. Hebrew was relegated to a religious and literary language. This is why, by the first century AD, Aramaic was the native tongue of a rabbi who with his followers caused a minor disturbance in Jerusalem at the time. In fact, Jesus’ sayings and parables recorded in the Gospels—written in Koine Greek—contain numerous stylistic traces from Aramaic. The Gospel of Mark and the Pauline Epistles include actual snippets of Aramaic, harking back to living memories of Jesus and the oral tradition received from him (e.g., see Mark 5:41 and Galatians 4:6).

Despite the ascendancy of Aramaic in daily life, Hebrew continued to be a fruitful medium for debate and composition, thanks to the Jewish rabbis.

The early third century AD saw the compilation of the Mishnah, a collection of rabbinic opinions on the Jewish law. Mishnaic Hebrew, or Rabbinic Hebrew, constitutes its own era in the evolution of the language. The Mishnah and its successor volume, the Gemara, form the Talmud, the most influential Hebrew text after the Bible itself.

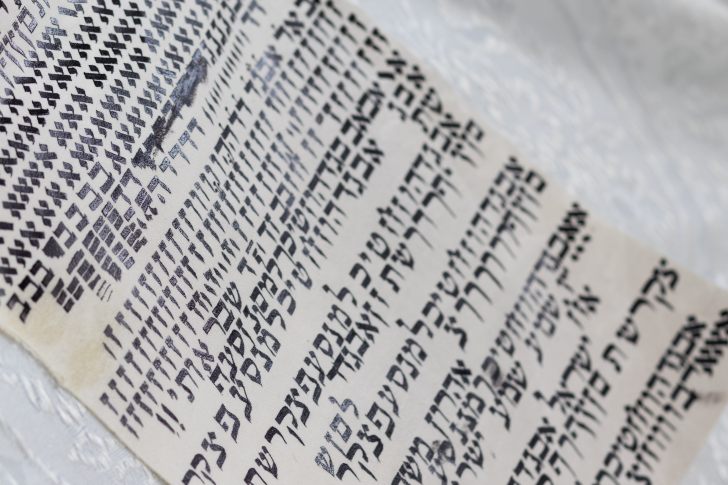

Hebrew remained in use throughout medieval times among Jewish communities. A group of scribes known as the Masoretes produced the most accurate copies of the biblical texts that we have today. Accomplished philosophers and Torah scholars like Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki (AD 1040–1105), better known by the acronym Rashi, and Rabbi Moses Maimonides (AD 1138–1204), aka the Rambam, wrote prolifically in Hebrew.

Although schools and synagogues were fertile ground for Hebrew use during this time, pure Hebrew wasn’t a vernacular. The Jewish diaspora spoke a variety of other languages, including Hebrew-Aramaic fusions with the dominant surrounding languages. Out of this interaction came Judeo-Arabic in the Middle East, Djudezmo (aka Judeo-Spanish) in Spain, and Yiddish, a German- and later Slavic-influenced tongue prevalent among Jews in Central and Eastern Europe. Traditionally, each of these languages was written in Hebrew script.

With increasing momentum for a Jewish state in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, there was a push to revive Hebrew as a spoken language. As you’d expect, Modern Hebrew has a much bigger vocabulary and has departed significantly from Ancient Hebrew in grammar, syntax, and semantics.

A Modern Hebrew speaker with a secular education can read biblical texts and recognize most of the words, but will likely struggle to interpret them due to shifts in word usage and now-defunct grammatical features present in ancient writing. Conversely, someone who only knows Biblical Hebrew will find many familiar words in modern speech, but will lack the necessary range and context to participate or make sense of it. For comparison, try getting around Athens today with Homer and Plato as your only background in Greek!

What should English speakers who are contemplating learning Biblical Hebrew know about the language?

For starters, the script runs right to left, not left to right. Written Hebrew is also an abjad, a system in which vowels aren’t marked. Since the oldest texts only record consonants, we don’t know the original pronunciation for many words (although scribes gradually developed a vowel marking system). As noted above, Hebrew also uses grammatical gender—nouns are always masculine or feminine.

Hebrew Vocabulary

We use a vocabulary learning platform to introduce students to new Hebrew terms. This software combines images and sounds with the target term, always used in a memorable context.

The combination of sounds and images allows students to quickly and enjoyably understand Hebrew words, in the ways that biblical writers used them. Our vocabulary learning platform is what flashcards want to be when they grow up!

Hebrew Grammar

In most courses, students are so burdened by grammar that they hardly get to enjoy actually reading in Biblical Hebrew. We want students to be exposed to grammar in such a way that it expands the range of Hebrew content they can successfully encounter.

Our Hebrew grammar platform grants students access to short lectures on Hebrew grammar that are characterized by clear explanations and helpful images. Then, you complete intuitive drill exercises that creatively combine sounds and images.

Active Pedagogy

All of our classes are live, online classes. Learning a language with other live people, plus the combination and careful sequencing of materials we employ, makes our classes highly productive and fun. In class, students see the vocabulary and grammar they have studied that week in a fresh and creative way, which prepares them to read their assigned texts with ease and success.

In every class session, students are also exposed to additional comprehensible input in a way that equips them to interact with Old Testament Hebrew actively. The best way to learn to read the language of the Jewish Scriptures is to speak and write it!

Comprehensible Input

The work of one of our heroes, the linguist Stephen Krashen (who has made all of his research on second language acquisition available for free), has convinced us that students acquire languages through extensive exposure to comprehensible input.

What does that mean? Basically, the more information in the target language you encounter, the faster you’ll learn. For our introductory course we’ve put together a sequence of readings and exercises that will equip you to read the entire book of Jonah in the original Hebrew with ease and enjoyment. And that’s just the introductory course.

Ready to learn Hebrew? The Torah, Nevi’im, and Ketuvim (and more!) are waiting…